Git on the Server

At this point, you should be able to do most of the day-to-day tasks for which you’ll be using Git. However, in order to do any collaboration in Git, you’ll need to have a remote Git repository. Although you can technically push changes to and pull changes from individuals' repositories, doing so is discouraged because you can fairly easily confuse what they’re working on if you’re not careful. Furthermore, you want your collaborators to be able to access the repository even if your computer is offline — having a more reliable common repository is often useful. Therefore, the preferred method for collaborating with someone is to set up an intermediate repository that you both have access to, and push to and pull from that.

Running a Git server is fairly straightforward. First, you choose which protocols you want your server to support. The first section of this chapter will cover the available protocols and the pros and cons of each. The next sections will explain some typical setups using those protocols and how to get your server running with them. Last, we’ll go over a few hosted options, if you don’t mind hosting your code on someone else’s server and don’t want to go through the hassle of setting up and maintaining your own server.

If you have no interest in running your own server, you can skip to the last section of the chapter to see some options for setting up a hosted account and then move on to the next chapter, where we discuss the various ins and outs of working in a distributed source control environment.

A remote repository is generally a bare repository — a Git repository that has no working directory.

Because the repository is only used as a collaboration point, there is no reason to have a snapshot checked out on disk; it’s just the Git data.

In the simplest terms, a bare repository is the contents of your project’s .git directory and nothing else.

The Protocols

Git can use four distinct protocols to transfer data: Local, HTTP, Secure Shell (SSH) and Git. Here we’ll discuss what they are and in what basic circumstances you would want (or not want) to use them.

Local Protocol

The most basic is the Local protocol, in which the remote repository is in another directory on the same host. This is often used if everyone on your team has access to a shared filesystem such as an NFS mount, or in the less likely case that everyone logs in to the same computer. The latter wouldn’t be ideal, because all your code repository instances would reside on the same computer, making a catastrophic loss much more likely.

If you have a shared mounted filesystem, then you can clone, push to, and pull from a local file-based repository. To clone a repository like this, or to add one as a remote to an existing project, use the path to the repository as the URL. For example, to clone a local repository, you can run something like this:

$ git clone /srv/git/project.git

Or you can do this:

$ git clone file:///srv/git/project.git

Git operates slightly differently if you explicitly specify file:// at the beginning of the URL.

If you just specify the path, Git tries to use hardlinks or directly copy the files it needs.

If you specify file://, Git fires up the processes that it normally uses to transfer data over a network, which is generally much less efficient.

The main reason to specify the file:// prefix is if you want a clean copy of the repository with extraneous references or objects left out — generally after an import from another VCS or something similar (see Git Internals for maintenance tasks).

We’ll use the normal path here because doing so is almost always faster.

To add a local repository to an existing Git project, you can run something like this:

$ git remote add local_proj /srv/git/project.git

Then, you can push to and pull from that remote via your new remote name local_proj as though you were doing so over a network.

The Pros

The pros of file-based repositories are that they’re simple and they use existing file permissions and network access. If you already have a shared filesystem to which your whole team has access, setting up a repository is very easy. You stick the bare repository copy somewhere everyone has shared access to and set the read/write permissions as you would for any other shared directory. We’ll discuss how to export a bare repository copy for this purpose in Getting Git on a Server.

This is also a nice option for quickly grabbing work from someone else’s working repository.

If you and a co-worker are working on the same project and they want you to check something out, running a command like git pull /home/john/project is often easier than them pushing to a remote server and you subsequently fetching from it.

The Cons

The cons of this method are that shared access is generally more difficult to set up and reach from multiple locations than basic network access. If you want to push from your laptop when you’re at home, you have to mount the remote disk, which can be difficult and slow compared to network-based access.

It’s important to mention that this isn’t necessarily the fastest option if you’re using a shared mount of some kind. A local repository is fast only if you have fast access to the data. A repository on NFS is often slower than the repository over SSH on the same server, allowing Git to run off local disks on each system.

Finally, this protocol does not protect the repository against accidental damage. Every user has full shell access to the ``remote'' directory, and there is nothing preventing them from changing or removing internal Git files and corrupting the repository.

The HTTP Protocols

Git can communicate over HTTP using two different modes. Prior to Git 1.6.6, there was only one way it could do this which was very simple and generally read-only. In version 1.6.6, a new, smarter protocol was introduced that involved Git being able to intelligently negotiate data transfer in a manner similar to how it does over SSH. In the last few years, this new HTTP protocol has become very popular since it’s simpler for the user and smarter about how it communicates. The newer version is often referred to as the Smart HTTP protocol and the older way as Dumb HTTP. We’ll cover the newer Smart HTTP protocol first.

Smart HTTP

Smart HTTP operates very similarly to the SSH or Git protocols but runs over standard HTTPS ports and can use various HTTP authentication mechanisms, meaning it’s often easier on the user than something like SSH, since you can use things like username/password authentication rather than having to set up SSH keys.

It has probably become the most popular way to use Git now, since it can be set up to both serve anonymously like the git:// protocol, and can also be pushed over with authentication and encryption like the SSH protocol.

Instead of having to set up different URLs for these things, you can now use a single URL for both.

If you try to push and the repository requires authentication (which it normally should), the server can prompt for a username and password.

The same goes for read access.

In fact, for services like GitHub, the URL you use to view the repository online (for example, https://github.com/schacon/simplegit) is the same URL you can use to clone and, if you have access, push over.

Dumb HTTP

If the server does not respond with a Git HTTP smart service, the Git client will try to fall back to the simpler Dumb HTTP protocol.

The Dumb protocol expects the bare Git repository to be served like normal files from the web server.

The beauty of Dumb HTTP is the simplicity of setting it up.

Basically, all you have to do is put a bare Git repository under your HTTP document root and set up a specific post-update hook, and you’re done (See Git Hooks).

At that point, anyone who can access the web server under which you put the repository can also clone your repository.

To allow read access to your repository over HTTP, do something like this:

$ cd /var/www/htdocs/ $ git clone --bare /path/to/git_project gitproject.git $ cd gitproject.git $ mv hooks/post-update.sample hooks/post-update $ chmod a+x hooks/post-update

That’s all.

The post-update hook that comes with Git by default runs the appropriate command (git update-server-info) to make HTTP fetching and cloning work properly.

This command is run when you push to this repository (over SSH perhaps); then, other people can clone via something like

$ git clone https://example.com/gitproject.git

In this particular case, we’re using the /var/www/htdocs path that is common for Apache setups, but you can use any static web server — just put the bare repository in its path.

The Git data is served as basic static files (see the Git Internals chapter for details about exactly how it’s served).

Generally you would either choose to run a read/write Smart HTTP server or simply have the files accessible as read-only in the Dumb manner. It’s rare to run a mix of the two services.

The Pros

We’ll concentrate on the pros of the Smart version of the HTTP protocol.

The simplicity of having a single URL for all types of access and having the server prompt only when authentication is needed makes things very easy for the end user. Being able to authenticate with a username and password is also a big advantage over SSH, since users don’t have to generate SSH keys locally and upload their public key to the server before being able to interact with it. For less sophisticated users, or users on systems where SSH is less common, this is a major advantage in usability. It is also a very fast and efficient protocol, similar to the SSH one.

You can also serve your repositories read-only over HTTPS, which means you can encrypt the content transfer; or you can go so far as to make the clients use specific signed SSL certificates.

Another nice thing is that HTTPS are such commonly used protocols that corporate firewalls are often set up to allow traffic through these ports.

The Cons

Git over HTTPS can be a little more tricky to set up compared to SSH on some servers. Other than that, there is very little advantage that other protocols have over Smart HTTP for serving Git content.

If you’re using HTTP for authenticated pushing, providing your credentials is sometimes more complicated than using keys over SSH. There are, however, several credential caching tools you can use, including Keychain access on macOS and Credential Manager on Windows, to make this pretty painless. Read Credential Storage to see how to set up secure HTTP password caching on your system.

The SSH Protocol

A common transport protocol for Git when self-hosting is over SSH. This is because SSH access to servers is already set up in most places — and if it isn’t, it’s easy to do. SSH is also an authenticated network protocol and, because it’s ubiquitous, it’s generally easy to set up and use.

To clone a Git repository over SSH, you can specify an ssh:// URL like this:

$ git clone ssh://[user@]server/project.git

Or you can use the shorter scp-like syntax for the SSH protocol:

$ git clone [user@]server:project.git

In both cases above, if you don’t specify the optional username, Git assumes the user you’re currently logged in as.

The Pros

The pros of using SSH are many. First, SSH is relatively easy to set up — SSH daemons are commonplace, many network admins have experience with them, and many OS distributions are set up with them or have tools to manage them. Next, access over SSH is secure — all data transfer is encrypted and authenticated. Last, like the HTTPS, Git and Local protocols, SSH is efficient, making the data as compact as possible before transferring it.

The Cons

The negative aspect of SSH is that it doesn’t support anonymous access to your Git repository. If you’re using SSH, people must have SSH access to your machine, even in a read-only capacity, which doesn’t make SSH conducive to open source projects for which people might simply want to clone your repository to examine it. If you’re using it only within your corporate network, SSH may be the only protocol you need to deal with. If you want to allow anonymous read-only access to your projects and also want to use SSH, you’ll have to set up SSH for you to push over but something else for others to fetch from.

The Git Protocol

Finally, we have the Git protocol.

This is a special daemon that comes packaged with Git; it listens on a dedicated port (9418) that provides a service similar to the SSH protocol, but with absolutely no authentication.

In order for a repository to be served over the Git protocol, you must create a git-daemon-export-ok file — the daemon won’t serve a repository without that file in it — but, other than that, there is no security.

Either the Git repository is available for everyone to clone, or it isn’t.

This means that there is generally no pushing over this protocol.

You can enable push access but, given the lack of authentication, anyone on the internet who finds your project’s URL could push to that project.

Suffice it to say that this is rare.

The Pros

The Git protocol is often the fastest network transfer protocol available. If you’re serving a lot of traffic for a public project or serving a very large project that doesn’t require user authentication for read access, it’s likely that you’ll want to set up a Git daemon to serve your project. It uses the same data-transfer mechanism as the SSH protocol but without the encryption and authentication overhead.

The Cons

The downside of the Git protocol is the lack of authentication.

It’s generally undesirable for the Git protocol to be the only access to your project.

Generally, you’ll pair it with SSH or HTTPS access for the few developers who have push (write) access and have everyone else use git:// for read-only access.

It’s also probably the most difficult protocol to set up.

It must run its own daemon, which requires xinetd or systemd configuration or the like, which isn’t always a walk in the park.

It also requires firewall access to port 9418, which isn’t a standard port that corporate firewalls always allow.

Behind big corporate firewalls, this obscure port is commonly blocked.

Getting Git on a Server

Now we’ll cover setting up a Git service running these protocols on your own server.

Here we’ll be demonstrating the commands and steps needed to do basic, simplified installations on a Linux-based server, though it’s also possible to run these services on macOS or Windows servers. Actually setting up a production server within your infrastructure will certainly entail differences in security measures or operating system tools, but hopefully this will give you the general idea of what’s involved.

In order to initially set up any Git server, you have to export an existing repository into a new bare repository — a repository that doesn’t contain a working directory.

This is generally straightforward to do.

In order to clone your repository to create a new bare repository, you run the clone command with the --bare option.

By convention, bare repository directory names end with the suffix .git, like so:

$ git clone --bare my_project my_project.git Cloning into bare repository 'my_project.git'... done.

You should now have a copy of the Git directory data in your my_project.git directory.

This is roughly equivalent to something like

$ cp -Rf my_project/.git my_project.git

There are a couple of minor differences in the configuration file but, for your purpose, this is close to the same thing. It takes the Git repository by itself, without a working directory, and creates a directory specifically for it alone.

Putting the Bare Repository on a Server

Now that you have a bare copy of your repository, all you need to do is put it on a server and set up your protocols.

Let’s say you’ve set up a server called git.example.com to which you have SSH access, and you want to store all your Git repositories under the /srv/git directory.

Assuming that /srv/git exists on that server, you can set up your new repository by copying your bare repository over:

$ scp -r my_project.git user@git.example.com:/srv/git

At this point, other users who have SSH-based read access to the /srv/git directory on that server can clone your repository by running

$ git clone user@git.example.com:/srv/git/my_project.git

If a user SSHs into a server and has write access to the /srv/git/my_project.git directory, they will also automatically have push access.

Git will automatically add group write permissions to a repository properly if you run the git init command with the --shared option.

Note that by running this command, you will not destroy any commits, refs, etc. in the process.

$ ssh user@git.example.com $ cd /srv/git/my_project.git $ git init --bare --shared

You see how easy it is to take a Git repository, create a bare version, and place it on a server to which you and your collaborators have SSH access. Now you’re ready to collaborate on the same project.

It’s important to note that this is literally all you need to do to run a useful Git server to which several people have access — just add SSH-able accounts on a server, and stick a bare repository somewhere that all those users have read and write access to. You’re ready to go — nothing else needed.

In the next few sections, you’ll see how to expand to more sophisticated setups. This discussion will include not having to create user accounts for each user, adding public read access to repositories, setting up web UIs and more. However, keep in mind that to collaborate with a couple of people on a private project, all you need is an SSH server and a bare repository.

Small Setups

If you’re a small outfit or are just trying out Git in your organization and have only a few developers, things can be simple for you. One of the most complicated aspects of setting up a Git server is user management. If you want some repositories to be read-only for certain users and read/write for others, access and permissions can be a bit more difficult to arrange.

SSH Access

If you have a server to which all your developers already have SSH access, it’s generally easiest to set up your first repository there, because you have to do almost no work (as we covered in the last section). If you want more complex access control type permissions on your repositories, you can handle them with the normal filesystem permissions of your server’s operating system.

If you want to place your repositories on a server that doesn’t have accounts for everyone on your team for whom you want to grant write access, then you must set up SSH access for them. We assume that if you have a server with which to do this, you already have an SSH server installed, and that’s how you’re accessing the server.

There are a few ways you can give access to everyone on your team.

The first is to set up accounts for everybody, which is straightforward but can be cumbersome.

You may not want to run adduser (or the possible alternative useradd) and have to set temporary passwords for every new user.

A second method is to create a single 'git' user account on the machine, ask every user who is to have write access to send you an SSH public key, and add that key to the ~/.ssh/authorized_keys file of that new 'git' account.

At that point, everyone will be able to access that machine via the 'git' account.

This doesn’t affect the commit data in any way — the SSH user you connect as doesn’t affect the commits you’ve recorded.

Another way to do it is to have your SSH server authenticate from an LDAP server or some other centralized authentication source that you may already have set up. As long as each user can get shell access on the machine, any SSH authentication mechanism you can think of should work.

Generating Your SSH Public Key

Many Git servers authenticate using SSH public keys.

In order to provide a public key, each user in your system must generate one if they don’t already have one.

This process is similar across all operating systems.

First, you should check to make sure you don’t already have a key.

By default, a user’s SSH keys are stored in that user’s ~/.ssh directory.

You can easily check to see if you have a key already by going to that directory and listing the contents:

$ cd ~/.ssh $ ls authorized_keys2 id_dsa known_hosts config id_dsa.pub

You’re looking for a pair of files named something like id_dsa or id_rsa and a matching file with a .pub extension.

The .pub file is your public key, and the other file is the corresponding private key.

If you don’t have these files (or you don’t even have a .ssh directory), you can create them by running a program called ssh-keygen, which is provided with the SSH package on Linux/macOS systems and comes with Git for Windows:

$ ssh-keygen -o Generating public/private rsa key pair. Enter file in which to save the key (/home/schacon/.ssh/id_rsa): Created directory '/home/schacon/.ssh'. Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase): Enter same passphrase again: Your identification has been saved in /home/schacon/.ssh/id_rsa. Your public key has been saved in /home/schacon/.ssh/id_rsa.pub. The key fingerprint is: d0:82:24:8e:d7:f1:bb:9b:33:53:96:93:49:da:9b:e3 schacon@mylaptop.local

First it confirms where you want to save the key (.ssh/id_rsa), and then it asks twice for a passphrase, which you can leave empty if you don’t want to type a password when you use the key.

However, if you do use a password, make sure to add the -o option; it saves the private key in a format that is more resistant to brute-force password cracking than is the default format.

You can also use the ssh-agent tool to prevent having to enter the password each time.

Now, each user that does this has to send their public key to you or whoever is administrating the Git server (assuming you’re using an SSH server setup that requires public keys).

All they have to do is copy the contents of the .pub file and email it.

The public keys look something like this:

$ cat ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAABIwAAAQEAklOUpkDHrfHY17SbrmTIpNLTGK9Tjom/BWDSU GPl+nafzlHDTYW7hdI4yZ5ew18JH4JW9jbhUFrviQzM7xlELEVf4h9lFX5QVkbPppSwg0cda3 Pbv7kOdJ/MTyBlWXFCR+HAo3FXRitBqxiX1nKhXpHAZsMciLq8V6RjsNAQwdsdMFvSlVK/7XA t3FaoJoAsncM1Q9x5+3V0Ww68/eIFmb1zuUFljQJKprrX88XypNDvjYNby6vw/Pb0rwert/En mZ+AW4OZPnTPI89ZPmVMLuayrD2cE86Z/il8b+gw3r3+1nKatmIkjn2so1d01QraTlMqVSsbx NrRFi9wrf+M7Q== schacon@mylaptop.local

For a more in-depth tutorial on creating an SSH key on multiple operating systems, see the GitHub guide on SSH keys at https://help.github.com/articles/generating-ssh-keys.

Setting Up the Server

Let’s walk through setting up SSH access on the server side.

In this example, you’ll use the authorized_keys method for authenticating your users.

We also assume you’re running a standard Linux distribution like Ubuntu.

A good deal of what is described here can be automated by using the ssh-copy-id command, rather than manually copying and installing public keys.

First, you create a git user account and a .ssh directory for that user.

$ sudo adduser git $ su git $ cd $ mkdir .ssh && chmod 700 .ssh $ touch .ssh/authorized_keys && chmod 600 .ssh/authorized_keys

Next, you need to add some developer SSH public keys to the authorized_keys file for the git user.

Let’s assume you have some trusted public keys and have saved them to temporary files.

Again, the public keys look something like this:

$ cat /tmp/id_rsa.john.pub ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABAQCB007n/ww+ouN4gSLKssMxXnBOvf9LGt4L ojG6rs6hPB09j9R/T17/x4lhJA0F3FR1rP6kYBRsWj2aThGw6HXLm9/5zytK6Ztg3RPKK+4k Yjh6541NYsnEAZuXz0jTTyAUfrtU3Z5E003C4oxOj6H0rfIF1kKI9MAQLMdpGW1GYEIgS9Ez Sdfd8AcCIicTDWbqLAcU4UpkaX8KyGlLwsNuuGztobF8m72ALC/nLF6JLtPofwFBlgc+myiv O7TCUSBdLQlgMVOFq1I2uPWQOkOWQAHukEOmfjy2jctxSDBQ220ymjaNsHT4kgtZg2AYYgPq dAv8JggJICUvax2T9va5 gsg-keypair

You just append them to the git user’s authorized_keys file in its .ssh directory:

$ cat /tmp/id_rsa.john.pub >> ~/.ssh/authorized_keys $ cat /tmp/id_rsa.josie.pub >> ~/.ssh/authorized_keys $ cat /tmp/id_rsa.jessica.pub >> ~/.ssh/authorized_keys

Now, you can set up an empty repository for them by running git init with the --bare option, which initializes the repository without a working directory:

$ cd /srv/git $ mkdir project.git $ cd project.git $ git init --bare Initialized empty Git repository in /srv/git/project.git/

Then, John, Josie, or Jessica can push the first version of their project into that repository by adding it as a remote and pushing up a branch.

Note that someone must shell onto the machine and create a bare repository every time you want to add a project.

Let’s use gitserver as the hostname of the server on which you’ve set up your git user and repository.

If you’re running it internally, and you set up DNS for gitserver to point to that server, then you can use the commands pretty much as is (assuming that myproject is an existing project with files in it):

# on John's computer $ cd myproject $ git init $ git add . $ git commit -m 'initial commit' $ git remote add origin git@gitserver:/srv/git/project.git $ git push origin master

At this point, the others can clone it down and push changes back up just as easily:

$ git clone git@gitserver:/srv/git/project.git $ cd project $ vim README $ git commit -am 'fix for the README file' $ git push origin master

With this method, you can quickly get a read/write Git server up and running for a handful of developers.

You should note that currently all these users can also log into the server and get a shell as the git user.

If you want to restrict that, you will have to change the shell to something else in the /etc/passwd file.

You can easily restrict the git user account to only Git-related activities with a limited shell tool called git-shell that comes with Git.

If you set this as the git user account’s login shell, then that account can’t have normal shell access to your server.

To use this, specify git-shell instead of bash or csh for that account’s login shell.

To do so, you must first add the full pathname of the git-shell command to /etc/shells if it’s not already there:

$ cat /etc/shells # see if git-shell is already in there. If not... $ which git-shell # make sure git-shell is installed on your system. $ sudo -e /etc/shells # and add the path to git-shell from last command

Now you can edit the shell for a user using chsh <username> -s <shell>:

$ sudo chsh git -s $(which git-shell)

Now, the git user can still use the SSH connection to push and pull Git repositories but can’t shell onto the machine.

If you try, you’ll see a login rejection like this:

$ ssh git@gitserver fatal: Interactive git shell is not enabled. hint: ~/git-shell-commands should exist and have read and execute access. Connection to gitserver closed.

At this point, users are still able to use SSH port forwarding to access any host the git server is able to reach.

If you want to prevent that, you can edit the authorized_keys file and prepend the following options to each key you’d like to restrict:

no-port-forwarding,no-X11-forwarding,no-agent-forwarding,no-pty

The result should look like this:

$ cat ~/.ssh/authorized_keys no-port-forwarding,no-X11-forwarding,no-agent-forwarding,no-pty ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABAQCB007n/ww+ouN4gSLKssMxXnBOvf9LGt4LojG6rs6h PB09j9R/T17/x4lhJA0F3FR1rP6kYBRsWj2aThGw6HXLm9/5zytK6Ztg3RPKK+4kYjh6541N YsnEAZuXz0jTTyAUfrtU3Z5E003C4oxOj6H0rfIF1kKI9MAQLMdpGW1GYEIgS9EzSdfd8AcC IicTDWbqLAcU4UpkaX8KyGlLwsNuuGztobF8m72ALC/nLF6JLtPofwFBlgc+myivO7TCUSBd LQlgMVOFq1I2uPWQOkOWQAHukEOmfjy2jctxSDBQ220ymjaNsHT4kgtZg2AYYgPqdAv8JggJ ICUvax2T9va5 gsg-keypair no-port-forwarding,no-X11-forwarding,no-agent-forwarding,no-pty ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABAQDEwENNMomTboYI+LJieaAY16qiXiH3wuvENhBG...

Now Git network commands will still work just fine but the users won’t be able to get a shell.

As the output states, you can also set up a directory in the git user’s home directory that customizes the git-shell command a bit.

For instance, you can restrict the Git commands that the server will accept or you can customize the message that users see if they try to SSH in like that.

Run git help shell for more information on customizing the shell.

Git Daemon

Next we’ll set up a daemon serving repositories using the ``Git'' protocol. This is a common choice for fast, unauthenticated access to your Git data. Remember that since this is not an authenticated service, anything you serve over this protocol is public within its network.

If you’re running this on a server outside your firewall, it should be used only for projects that are publicly visible to the world. If the server you’re running it on is inside your firewall, you might use it for projects that a large number of people or computers (continuous integration or build servers) have read-only access to, when you don’t want to have to add an SSH key for each.

In any case, the Git protocol is relatively easy to set up. Basically, you need to run this command in a daemonized manner:

$ git daemon --reuseaddr --base-path=/srv/git/ /srv/git/

The --reuseaddr option allows the server to restart without waiting for old connections to time out, while the --base-path option allows people to clone projects without specifying the entire path, and the path at the end tells the Git daemon where to look for repositories to export.

If you’re running a firewall, you’ll also need to punch a hole in it at port 9418 on the box you’re setting this up on.

You can daemonize this process a number of ways, depending on the operating system you’re running.

Since systemd is the most common init system among modern Linux distributions, you can use it for that purpose.

Simply place a file in /etc/systemd/system/git-daemon.service with these contents:

[Unit] Description=Start Git Daemon [Service] ExecStart=/usr/bin/git daemon --reuseaddr --base-path=/srv/git/ /srv/git/ Restart=always RestartSec=500ms StandardOutput=syslog StandardError=syslog SyslogIdentifier=git-daemon User=git Group=git [Install] WantedBy=multi-user.target

You might have noticed that Git daemon is started here with git as both group and user.

Modify it to fit your needs and make sure the provided user exists on the system.

Also, check that the Git binary is indeed located at /usr/bin/git and change the path if necessary.

Finally, you’ll run systemctl enable git-daemon to automatically start the service on boot, and can start and stop the service with, respectively, systemctl start git-daemon and systemctl stop git-daemon.

On other systems, you may want to use xinetd, a script in your sysvinit system, or something else — as long as you get that command daemonized and watched somehow.

Next, you have to tell Git which repositories to allow unauthenticated Git server-based access to.

You can do this in each repository by creating a file named git-daemon-export-ok.

$ cd /path/to/project.git $ touch git-daemon-export-ok

The presence of that file tells Git that it’s OK to serve this project without authentication.

Smart HTTP

We now have authenticated access through SSH and unauthenticated access through git://, but there is also a protocol that can do both at the same time.

Setting up Smart HTTP is basically just enabling a CGI script that is provided with Git called git-http-backend on the server.

This CGI will read the path and headers sent by a git fetch or git push to an HTTP URL and determine if the client can communicate over HTTP (which is true for any client since version 1.6.6).

If the CGI sees that the client is smart, it will communicate smartly with it; otherwise it will fall back to the dumb behavior (so it is backward compatible for reads with older clients).

Let’s walk through a very basic setup. We’ll set this up with Apache as the CGI server. If you don’t have Apache setup, you can do so on a Linux box with something like this:

$ sudo apt-get install apache2 apache2-utils $ a2enmod cgi alias env

This also enables the mod_cgi, mod_alias, and mod_env modules, which are all needed for this to work properly.

You’ll also need to set the Unix user group of the /srv/git directories to www-data so your web server can read- and write-access the repositories, because the Apache instance running the CGI script will (by default) be running as that user:

$ chgrp -R www-data /srv/git

Next we need to add some things to the Apache configuration to run the git-http-backend as the handler for anything coming into the /git path of your web server.

SetEnv GIT_PROJECT_ROOT /srv/git SetEnv GIT_HTTP_EXPORT_ALL ScriptAlias /git/ /usr/lib/git-core/git-http-backend/

If you leave out GIT_HTTP_EXPORT_ALL environment variable, then Git will only serve to unauthenticated clients the repositories with the git-daemon-export-ok file in them, just like the Git daemon did.

Finally you’ll want to tell Apache to allow requests to git-http-backend and make writes be authenticated somehow, possibly with an Auth block like this:

<Files "git-http-backend">

AuthType Basic

AuthName "Git Access"

AuthUserFile /srv/git/.htpasswd

Require expr !(%{QUERY_STRING} -strmatch '*service=git-receive-pack*' || %{REQUEST_URI} =~ m#/git-receive-pack$#)

Require valid-user

</Files>

That will require you to create a .htpasswd file containing the passwords of all the valid users.

Here is an example of adding a ``schacon'' user to the file:

$ htpasswd -c /srv/git/.htpasswd schacon

There are tons of ways to have Apache authenticate users, you’ll have to choose and implement one of them. This is just the simplest example we could come up with. You’ll also almost certainly want to set this up over SSL so all this data is encrypted.

We don’t want to go too far down the rabbit hole of Apache configuration specifics, since you could well be using a different server or have different authentication needs.

The idea is that Git comes with a CGI called git-http-backend that when invoked will do all the negotiation to send and receive data over HTTP.

It does not implement any authentication itself, but that can easily be controlled at the layer of the web server that invokes it.

You can do this with nearly any CGI-capable web server, so go with the one that you know best.

For more information on configuring authentication in Apache, check out the Apache docs here: https://httpd.apache.org/docs/current/howto/auth.html

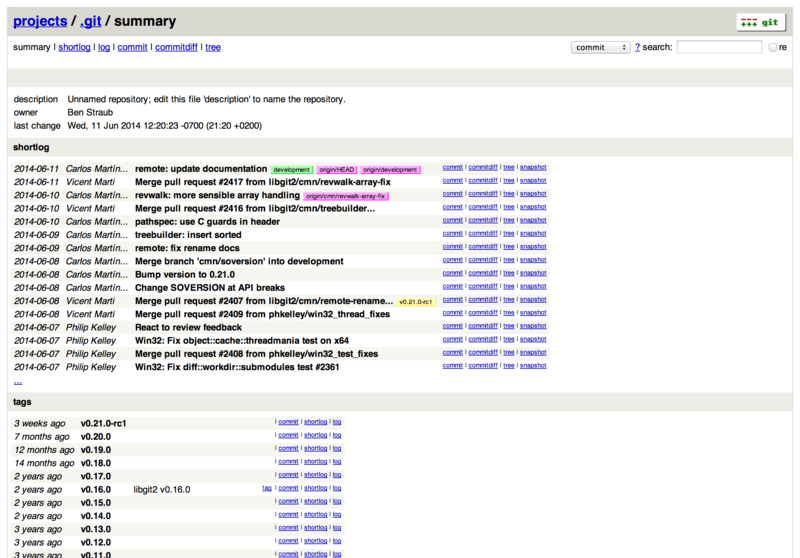

GitWeb

Now that you have basic read/write and read-only access to your project, you may want to set up a simple web-based visualizer. Git comes with a CGI script called GitWeb that is sometimes used for this.

If you want to check out what GitWeb would look like for your project, Git comes with a command to fire up a temporary instance if you have a lightweight web server on your system like lighttpd or webrick.

On Linux machines, lighttpd is often installed, so you may be able to get it to run by typing git instaweb in your project directory.

If you’re running a Mac, Leopard comes preinstalled with Ruby, so webrick may be your best bet.

To start instaweb with a non-lighttpd handler, you can run it with the --httpd option.

$ git instaweb --httpd=webrick [2009-02-21 10:02:21] INFO WEBrick 1.3.1 [2009-02-21 10:02:21] INFO ruby 1.8.6 (2008-03-03) [universal-darwin9.0]

That starts up an HTTPD server on port 1234 and then automatically starts a web browser that opens on that page.

It’s pretty easy on your part.

When you’re done and want to shut down the server, you can run the same command with the --stop option:

$ git instaweb --httpd=webrick --stop

If you want to run the web interface on a server all the time for your team or for an open source project you’re hosting, you’ll need to set up the CGI script to be served by your normal web server.

Some Linux distributions have a gitweb package that you may be able to install via apt or dnf, so you may want to try that first.

We’ll walk through installing GitWeb manually very quickly.

First, you need to get the Git source code, which GitWeb comes with, and generate the custom CGI script:

$ git clone git://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/git/git.git

$ cd git/

$ make GITWEB_PROJECTROOT="/srv/git" prefix=/usr gitweb

SUBDIR gitweb

SUBDIR ../

make[2]: `GIT-VERSION-FILE' is up to date.

GEN gitweb.cgi

GEN static/gitweb.js

$ sudo cp -Rf gitweb /var/www/

Notice that you have to tell the command where to find your Git repositories with the GITWEB_PROJECTROOT variable.

Now, you need to make Apache use CGI for that script, for which you can add a VirtualHost:

<VirtualHost *:80>

ServerName gitserver

DocumentRoot /var/www/gitweb

<Directory /var/www/gitweb>

Options +ExecCGI +FollowSymLinks +SymLinksIfOwnerMatch

AllowOverride All

order allow,deny

Allow from all

AddHandler cgi-script cgi

DirectoryIndex gitweb.cgi

</Directory>

</VirtualHost>

Again, GitWeb can be served with any CGI or Perl capable web server; if you prefer to use something else, it shouldn’t be difficult to set up.

At this point, you should be able to visit http://gitserver/ to view your repositories online.

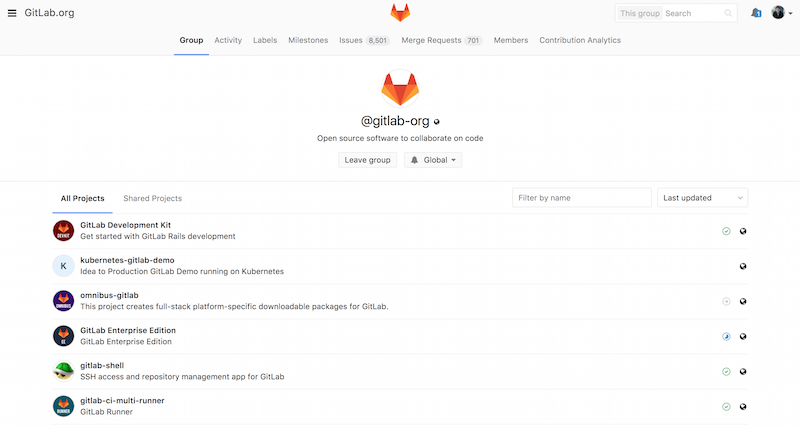

GitLab

GitWeb is pretty simplistic though. If you’re looking for a more modern, fully featured Git server, there are some several open source solutions out there that you can install instead. As GitLab is one of the more popular ones, we’ll cover installing and using it as an example. This is a bit more complex than the GitWeb option and likely requires more maintenance, but it is a much more fully featured option.

Installation

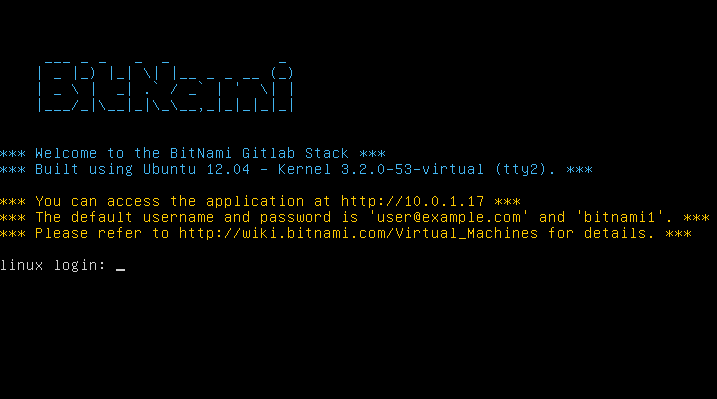

GitLab is a database-backed web application, so its installation is a bit more involved than some other Git servers. Fortunately, this process is very well-documented and supported.

There are a few methods you can pursue to install GitLab. To get something up and running quickly, you can download a virtual machine image or a one-click installer from https://bitnami.com/stack/gitlab, and tweak the configuration to match your particular environment. One nice touch Bitnami has included is the login screen (accessed by typing alt+→); it tells you the IP address and default username and password for the installed GitLab.

For anything else, follow the guidance in the GitLab Community Edition readme, which can be found at https://gitlab.com/gitlab-org/gitlab-ce/tree/master. There you’ll find assistance for installing GitLab using Chef recipes, a virtual machine on Digital Ocean, and RPM and DEB packages (which, as of this writing, are in beta). There’s also ``unofficial'' guidance on getting GitLab running with non-standard operating systems and databases, a fully-manual installation script, and many other topics.

Administration

GitLab’s administration interface is accessed over the web.

Simply point your browser to the hostname or IP address where GitLab is installed, and log in as an admin user.

The default username is admin@local.host, and the default password is 5iveL!fe (which you will be prompted to change as soon as you enter it).

Once logged in, click the ``Admin area'' icon in the menu at the top right.

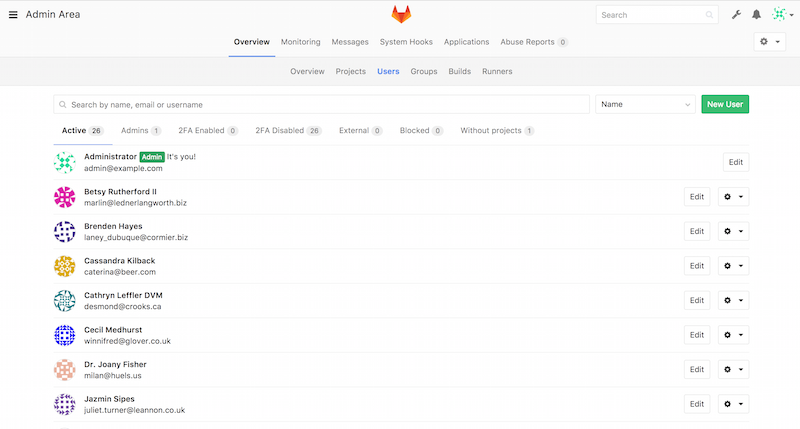

Users

Users in GitLab are accounts that correspond to people.

User accounts don’t have a lot of complexity; mainly it’s a collection of personal information attached to login data.

Each user account comes with a namespace, which is a logical grouping of projects that belong to that user.

If the user jane had a project named project, that project’s url would be http://server/jane/project.

Removing a user can be done in two ways. ``Blocking'' a user prevents them from logging into the GitLab instance, but all of the data under that user’s namespace will be preserved, and commits signed with that user’s email address will still link back to their profile.

``Destroying'' a user, on the other hand, completely removes them from the database and filesystem. All projects and data in their namespace is removed, and any groups they own will also be removed. This is obviously a much more permanent and destructive action, and its uses are rare.

Groups

A GitLab group is an assemblage of projects, along with data about how users can access those projects.

Each group has a project namespace (the same way that users do), so if the group training has a project materials, its url would be http://server/training/materials.

Each group is associated with a number of users, each of which has a level of permissions for the group’s projects and the group itself.

These range from Guest'' (issues and chat only) to Owner'' (full control of the group, its members, and its projects).

The types of permissions are too numerous to list here, but GitLab has a helpful link on the administration screen.

Projects

A GitLab project roughly corresponds to a single Git repository. Every project belongs to a single namespace, either a user or a group. If the project belongs to a user, the owner of the project has direct control over who has access to the project; if the project belongs to a group, the group’s user-level permissions will also take effect.

Every project also has a visibility level, which controls who has read access to that project’s pages and repository.

If a project is Private, the project’s owner must explicitly grant access to specific users.

An Internal project is visible to any logged-in user, and a Public project is visible to anyone.

Note that this controls both git fetch access as well as access to the web UI for that project.

Hooks

GitLab includes support for hooks, both at a project or system level. For either of these, the GitLab server will perform an HTTP POST with some descriptive JSON whenever relevant events occur. This is a great way to connect your Git repositories and GitLab instance to the rest of your development automation, such as CI servers, chat rooms, or deployment tools.

Basic Usage

The first thing you’ll want to do with GitLab is create a new project.

This is accomplished by clicking the +'' icon on the toolbar.

You’ll be asked for the project’s name, which namespace it should belong to, and what its visibility level should be.

Most of what you specify here isn’t permanent, and can be re-adjusted later through the settings interface.

Click Create Project'', and you’re done.

Once the project exists, you’ll probably want to connect it with a local Git repository.

Each project is accessible over HTTPS or SSH, either of which can be used to configure a Git remote.

The URLs are visible at the top of the project’s home page.

For an existing local repository, this command will create a remote named gitlab to the hosted location:

$ git remote add gitlab https://server/namespace/project.git

If you don’t have a local copy of the repository, you can simply do this:

$ git clone https://server/namespace/project.git

The web UI provides access to several useful views of the repository itself. Each project’s home page shows recent activity, and links along the top will lead you to views of the project’s files and commit log.

Working Together

The simplest way of working together on a GitLab project is by giving another user direct push access to the Git repository.

You can add a user to a project by going to the Members'' section of that project’s settings, and associating the new user with an access level (the different access levels are discussed a bit in Groups).

By giving a user an access level of Developer'' or above, that user can push commits and branches directly to the repository with impunity.

Another, more decoupled way of collaboration is by using merge requests.

This feature enables any user that can see a project to contribute to it in a controlled way.

Users with direct access can simply create a branch, push commits to it, and open a merge request from their branch back into master or any other branch.

Users who don’t have push permissions for a repository can ``fork'' it (create their own copy), push commits to that copy, and open a merge request from their fork back to the main project.

This model allows the owner to be in full control of what goes into the repository and when, while allowing contributions from untrusted users.

Merge requests and issues are the main units of long-lived discussion in GitLab. Each merge request allows a line-by-line discussion of the proposed change (which supports a lightweight kind of code review), as well as a general overall discussion thread. Both can be assigned to users, or organized into milestones.

This section is focused mainly on the Git-related features of GitLab, but as a mature project, it provides many other features to help your team work together, such as project wikis and system maintenance tools. One benefit to GitLab is that, once the server is set up and running, you’ll rarely need to tweak a configuration file or access the server via SSH; most administration and general usage can be accomplished through the in-browser interface.

Third Party Hosted Options

If you don’t want to go through all of the work involved in setting up your own Git server, you have several options for hosting your Git projects on an external dedicated hosting site. Doing so offers a number of advantages: a hosting site is generally quick to set up and easy to start projects on, and no server maintenance or monitoring is involved. Even if you set up and run your own server internally, you may still want to use a public hosting site for your open source code – it’s generally easier for the open source community to find and help you with.

These days, you have a huge number of hosting options to choose from, each with different advantages and disadvantages. To see an up-to-date list, check out the GitHosting page on the main Git wiki at https://git.wiki.kernel.org/index.php/GitHosting

We’ll cover using GitHub in detail in GitHub, as it is the largest Git host out there and you may need to interact with projects hosted on it in any case, but there are dozens more to choose from should you not want to set up your own Git server.

Summary

You have several options to get a remote Git repository up and running so that you can collaborate with others or share your work.

Running your own server gives you a lot of control and allows you to run the server within your own firewall, but such a server generally requires a fair amount of your time to set up and maintain. If you place your data on a hosted server, it’s easy to set up and maintain; however, you have to be able to keep your code on someone else’s servers, and some organizations don’t allow that.

It should be fairly straightforward to determine which solution or combination of solutions is appropriate for you and your organization.