Distributed Git

Now that you have a remote Git repository set up as a focal point for all the developers to share their code, and you’re familiar with basic Git commands in a local workflow, you’ll look at how to utilize some of the distributed workflows that Git affords you.

In this chapter, you’ll see how to work with Git in a distributed environment as a contributor and an integrator. That is, you’ll learn how to contribute code successfully to a project and make it as easy on you and the project maintainer as possible, and also how to maintain a project successfully with a number of developers contributing.

Distributed Workflows

In contrast with Centralized Version Control Systems (CVCSs), the distributed nature of Git allows you to be far more flexible in how developers collaborate on projects. In centralized systems, every developer is a node working more or less equally with a central hub. In Git, however, every developer is potentially both a node and a hub; that is, every developer can both contribute code to other repositories and maintain a public repository on which others can base their work and which they can contribute to. This presents a vast range of workflow possibilities for your project and/or your team, so we’ll cover a few common paradigms that take advantage of this flexibility. We’ll go over the strengths and possible weaknesses of each design; you can choose a single one to use, or you can mix and match features from each.

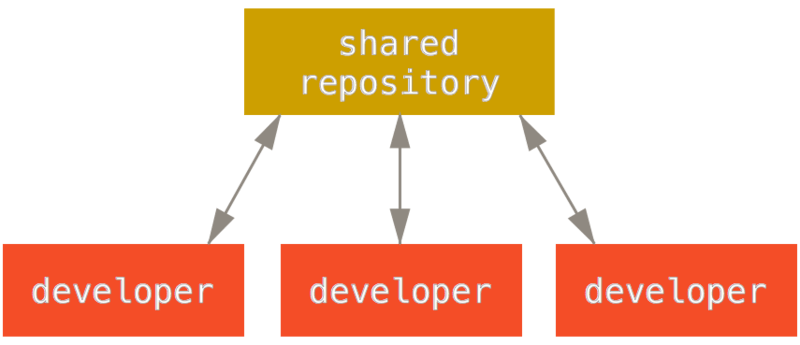

Centralized Workflow

In centralized systems, there is generally a single collaboration model — the centralized workflow. One central hub, or repository, can accept code, and everyone synchronizes their work with it. A number of developers are nodes — consumers of that hub — and synchronize with that centralized location.

This means that if two developers clone from the hub and both make changes, the first developer to push their changes back up can do so with no problems. The second developer must merge in the first one’s work before pushing changes up, so as not to overwrite the first developer’s changes. This concept is as true in Git as it is in Subversion (or any CVCS), and this model works perfectly well in Git.

If you are already comfortable with a centralized workflow in your company or team, you can easily continue using that workflow with Git. Simply set up a single repository, and give everyone on your team push access; Git won’t let users overwrite each other.

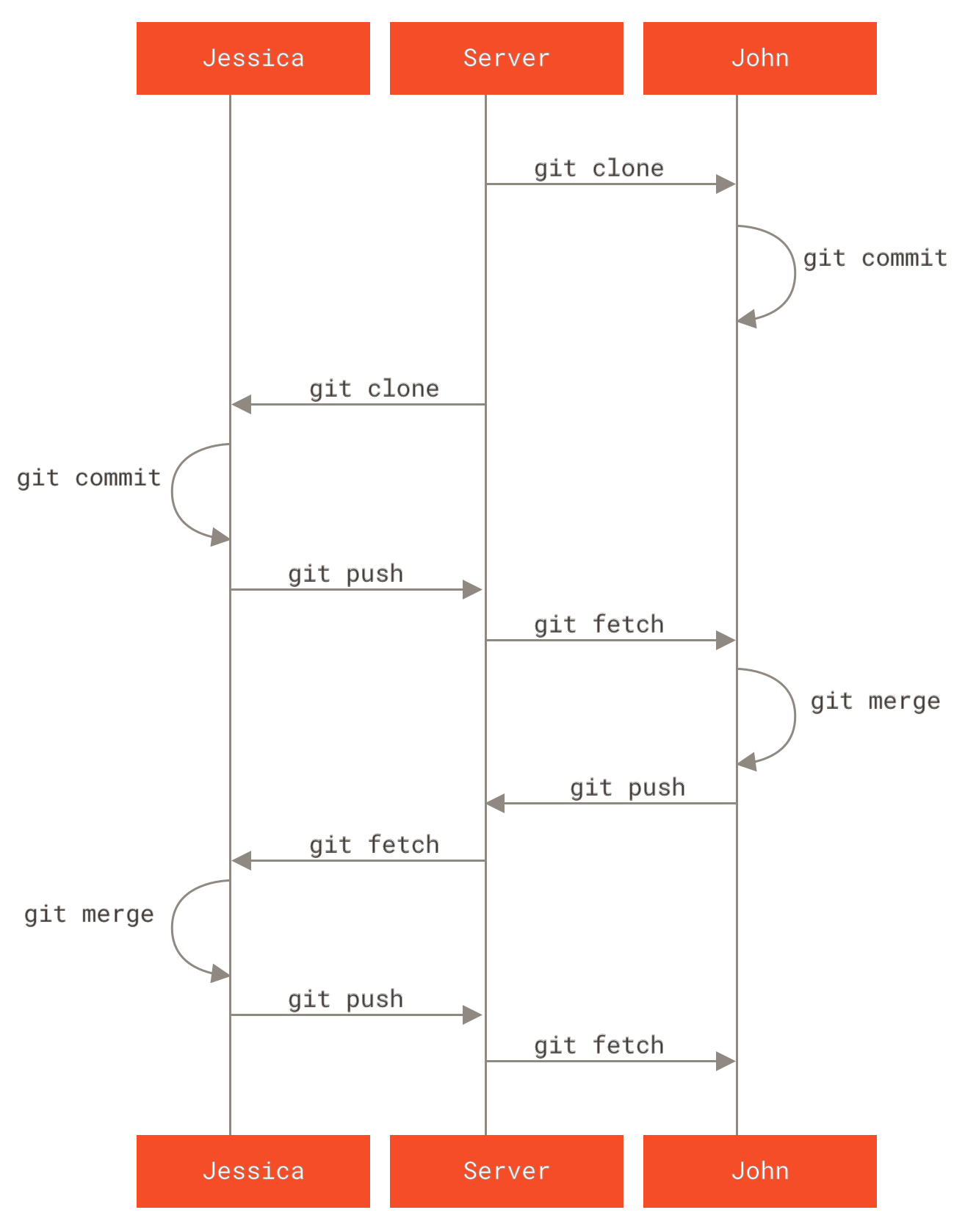

Say John and Jessica both start working at the same time. John finishes his change and pushes it to the server. Then Jessica tries to push her changes, but the server rejects them. She is told that she’s trying to push non-fast-forward changes and that she won’t be able to do so until she fetches and merges. This workflow is attractive to a lot of people because it’s a paradigm that many are familiar and comfortable with.

This is also not limited to small teams. With Git’s branching model, it’s possible for hundreds of developers to successfully work on a single project through dozens of branches simultaneously.

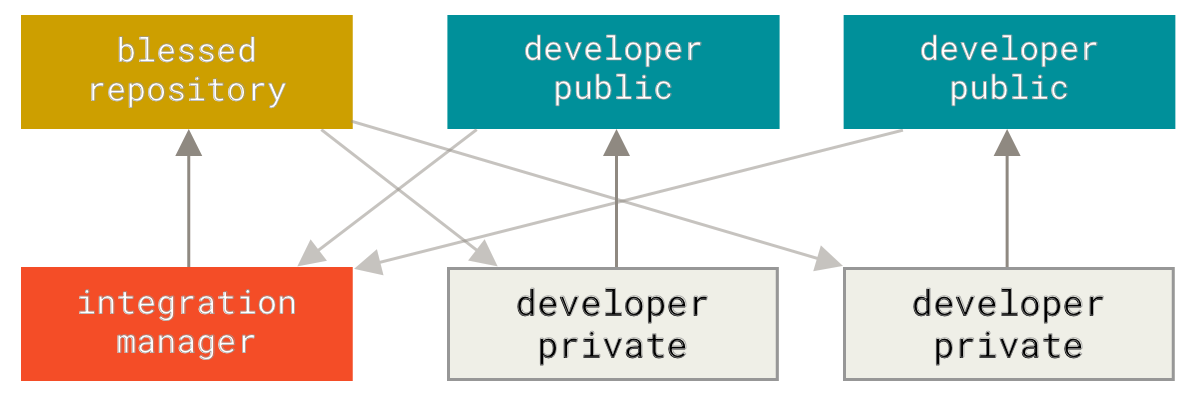

Integration-Manager Workflow

Because Git allows you to have multiple remote repositories, it’s possible to have a workflow where each developer has write access to their own public repository and read access to everyone else’s. This scenario often includes a canonical repository that represents the ``official'' project. To contribute to that project, you create your own public clone of the project and push your changes to it. Then, you can send a request to the maintainer of the main project to pull in your changes. The maintainer can then add your repository as a remote, test your changes locally, merge them into their branch, and push back to their repository. The process works as follows (see Integration-manager workflow.):

-

The project maintainer pushes to their public repository.

-

A contributor clones that repository and makes changes.

-

The contributor pushes to their own public copy.

-

The contributor sends the maintainer an email asking them to pull changes.

-

The maintainer adds the contributor’s repository as a remote and merges locally.

-

The maintainer pushes merged changes to the main repository.

This is a very common workflow with hub-based tools like GitHub or GitLab, where it’s easy to fork a project and push your changes into your fork for everyone to see. One of the main advantages of this approach is that you can continue to work, and the maintainer of the main repository can pull in your changes at any time. Contributors don’t have to wait for the project to incorporate their changes — each party can work at their own pace.

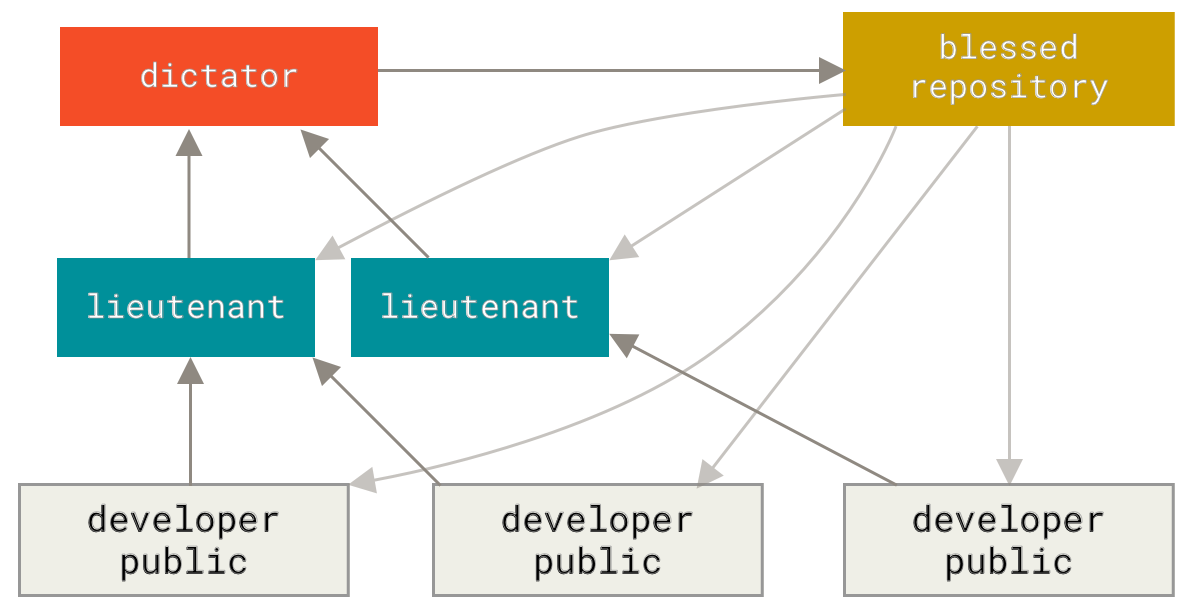

Dictator and Lieutenants Workflow

This is a variant of a multiple-repository workflow. It’s generally used by huge projects with hundreds of collaborators; one famous example is the Linux kernel. Various integration managers are in charge of certain parts of the repository; they’re called lieutenants. All the lieutenants have one integration manager known as the benevolent dictator. The benevolent dictator pushes from their directory to a reference repository from which all the collaborators need to pull. The process works like this (see Benevolent dictator workflow.):

-

Regular developers work on their topic branch and rebase their work on top of

master. Themasterbranch is that of the reference repository to which the dictator pushes. -

Lieutenants merge the developers' topic branches into their

masterbranch. -

The dictator merges the lieutenants'

masterbranches into the dictator’smasterbranch. -

Finally, the dictator pushes that

masterbranch to the reference repository so the other developers can rebase on it.

This kind of workflow isn’t common, but can be useful in very big projects, or in highly hierarchical environments. It allows the project leader (the dictator) to delegate much of the work and collect large subsets of code at multiple points before integrating them.

Workflows Summary

These are some commonly used workflows that are possible with a distributed system like Git, but you can see that many variations are possible to suit your particular real-world workflow. Now that you can (hopefully) determine which workflow combination may work for you, we’ll cover some more specific examples of how to accomplish the main roles that make up the different flows. In the next section, you’ll learn about a few common patterns for contributing to a project.

Contributing to a Project

The main difficulty with describing how to contribute to a project are the numerous variations on how to do that. Because Git is very flexible, people can and do work together in many ways, and it’s problematic to describe how you should contribute — every project is a bit different. Some of the variables involved are active contributor count, chosen workflow, your commit access, and possibly the external contribution method.

The first variable is active contributor count — how many users are actively contributing code to this project, and how often? In many instances, you’ll have two or three developers with a few commits a day, or possibly less for somewhat dormant projects. For larger companies or projects, the number of developers could be in the thousands, with hundreds or thousands of commits coming in each day. This is important because with more and more developers, you run into more issues with making sure your code applies cleanly or can be easily merged. Changes you submit may be rendered obsolete or severely broken by work that is merged in while you were working or while your changes were waiting to be approved or applied. How can you keep your code consistently up to date and your commits valid?

The next variable is the workflow in use for the project. Is it centralized, with each developer having equal write access to the main codeline? Does the project have a maintainer or integration manager who checks all the patches? Are all the patches peer-reviewed and approved? Are you involved in that process? Is a lieutenant system in place, and do you have to submit your work to them first?

The next variable is your commit access. The workflow required in order to contribute to a project is much different if you have write access to the project than if you don’t. If you don’t have write access, how does the project prefer to accept contributed work? Does it even have a policy? How much work are you contributing at a time? How often do you contribute?

All these questions can affect how you contribute effectively to a project and what workflows are preferred or available to you. We’ll cover aspects of each of these in a series of use cases, moving from simple to more complex; you should be able to construct the specific workflows you need in practice from these examples.

Commit Guidelines

Before we start looking at the specific use cases, here’s a quick note about commit messages.

Having a good guideline for creating commits and sticking to it makes working with Git and collaborating with others a lot easier.

The Git project provides a document that lays out a number of good tips for creating commits from which to submit patches — you can read it in the Git source code in the Documentation/SubmittingPatches file.

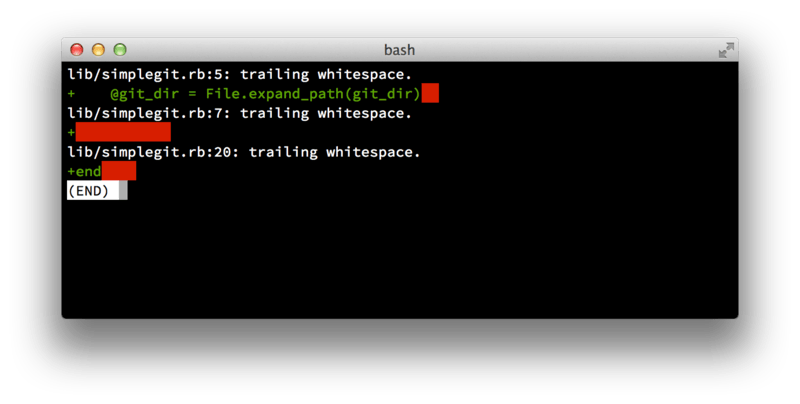

First, your submissions should not contain any whitespace errors.

Git provides an easy way to check for this — before you commit, run git diff --check, which identifies possible whitespace errors and lists them for you.

git diff --check.If you run that command before committing, you can tell if you’re about to commit whitespace issues that may annoy other developers.

Next, try to make each commit a logically separate changeset.

If you can, try to make your changes digestible — don’t code for a whole weekend on five different issues and then submit them all as one massive commit on Monday.

Even if you don’t commit during the weekend, use the staging area on Monday to split your work into at least one commit per issue, with a useful message per commit.

If some of the changes modify the same file, try to use git add --patch to partially stage files (covered in detail in Interactive Staging).

The project snapshot at the tip of the branch is identical whether you do one commit or five, as long as all the changes are added at some point, so try to make things easier on your fellow developers when they have to review your changes.

This approach also makes it easier to pull out or revert one of the changesets if you need to later. Rewriting History describes a number of useful Git tricks for rewriting history and interactively staging files — use these tools to help craft a clean and understandable history before sending the work to someone else.

The last thing to keep in mind is the commit message. Getting in the habit of creating quality commit messages makes using and collaborating with Git a lot easier. As a general rule, your messages should start with a single line that’s no more than about 50 characters and that describes the changeset concisely, followed by a blank line, followed by a more detailed explanation. The Git project requires that the more detailed explanation include your motivation for the change and contrast its implementation with previous behavior — this is a good guideline to follow. Write your commit message in the imperative: "Fix bug" and not "Fixed bug" or "Fixes bug." Here is a template originally written by Tim Pope:

Capitalized, short (50 chars or less) summary More detailed explanatory text, if necessary. Wrap it to about 72 characters or so. In some contexts, the first line is treated as the subject of an email and the rest of the text as the body. The blank line separating the summary from the body is critical (unless you omit the body entirely); tools like rebase can get confused if you run the two together. Write your commit message in the imperative: "Fix bug" and not "Fixed bug" or "Fixes bug." This convention matches up with commit messages generated by commands like git merge and git revert. Further paragraphs come after blank lines. - Bullet points are okay, too - Typically a hyphen or asterisk is used for the bullet, followed by a single space, with blank lines in between, but conventions vary here - Use a hanging indent

If all your commit messages follow this model, things will be much easier for you and the developers with whom you collaborate.

The Git project has well-formatted commit messages — try running git log --no-merges there to see what a nicely-formatted project-commit history looks like.

Do as we say, not as we do.

For the sake of brevity, many of the examples in this book don’t have nicely-formatted commit messages like this; instead, we simply use the -m option to git commit.

In short, do as we say, not as we do.

Private Small Team

The simplest setup you’re likely to encounter is a private project with one or two other developers. ``Private,'' in this context, means closed-source — not accessible to the outside world. You and the other developers all have push access to the repository.

In this environment, you can follow a workflow similar to what you might do when using Subversion or another centralized system.

You still get the advantages of things like offline committing and vastly simpler branching and merging, but the workflow can be very similar; the main difference is that merges happen client-side rather than on the server at commit time.

Let’s see what it might look like when two developers start to work together with a shared repository.

The first developer, John, clones the repository, makes a change, and commits locally.

(The protocol messages have been replaced with … in these examples to shorten them somewhat.)

# John's Machine $ git clone john@githost:simplegit.git Cloning into 'simplegit'... ... $ cd simplegit/ $ vim lib/simplegit.rb $ git commit -am 'remove invalid default value' [master 738ee87] remove invalid default value 1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)

The second developer, Jessica, does the same thing — clones the repository and commits a change:

# Jessica's Machine $ git clone jessica@githost:simplegit.git Cloning into 'simplegit'... ... $ cd simplegit/ $ vim TODO $ git commit -am 'add reset task' [master fbff5bc] add reset task 1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

Now, Jessica pushes her work to the server, which works just fine:

# Jessica's Machine $ git push origin master ... To jessica@githost:simplegit.git 1edee6b..fbff5bc master -> master

The last line of the output above shows a useful return message from the push operation.

The basic format is <oldref>..<newref> fromref → toref, where oldref means the old reference, newref means the new reference, fromref is the name of the local reference being pushed, and toref is the name of the remote reference being updated.

You’ll see similar output like this below in the discussions, so having a basic idea of the meaning will help in understanding the various states of the repositories.

More details are available in the documentation for git-push.

Continuing with this example, shortly afterwards, John makes some changes, commits them to his local repository, and tries to push them to the same server:

# John's Machine $ git push origin master To john@githost:simplegit.git ! [rejected] master -> master (non-fast forward) error: failed to push some refs to 'john@githost:simplegit.git'

In this case, John’s push fails because of Jessica’s earlier push of her changes. This is especially important to understand if you’re used to Subversion, because you’ll notice that the two developers didn’t edit the same file. Although Subversion automatically does such a merge on the server if different files are edited, with Git, you must first merge the commits locally. In other words, John must first fetch Jessica’s upstream changes and merge them into his local repository before he will be allowed to push.

As a first step, John fetches Jessica’s work (this only fetches Jessica’s upstream work, it does not yet merge it into John’s work):

$ git fetch origin ... From john@githost:simplegit + 049d078...fbff5bc master -> origin/master

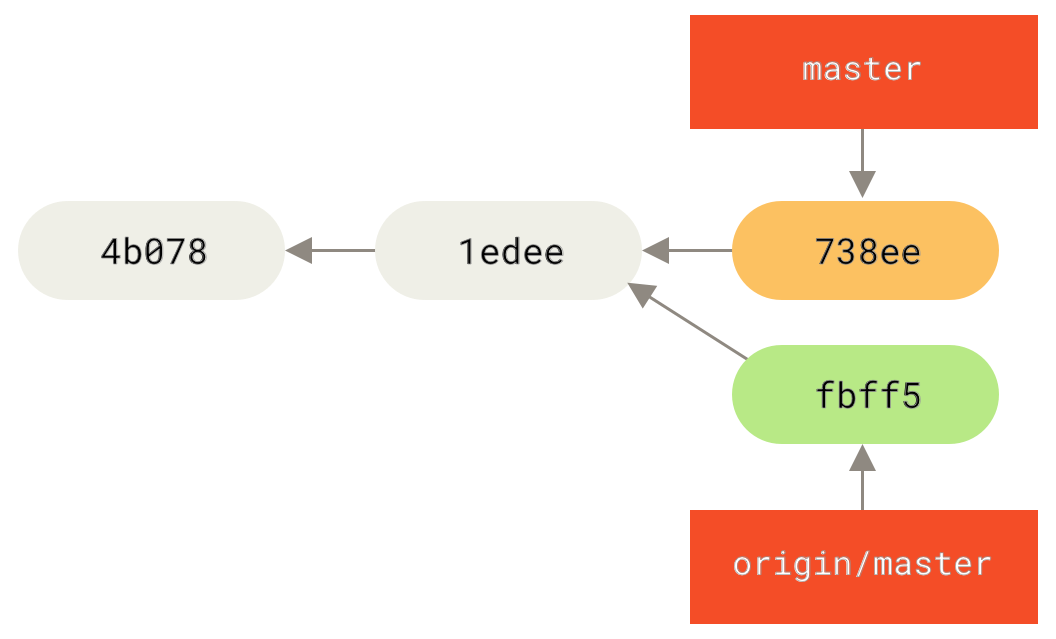

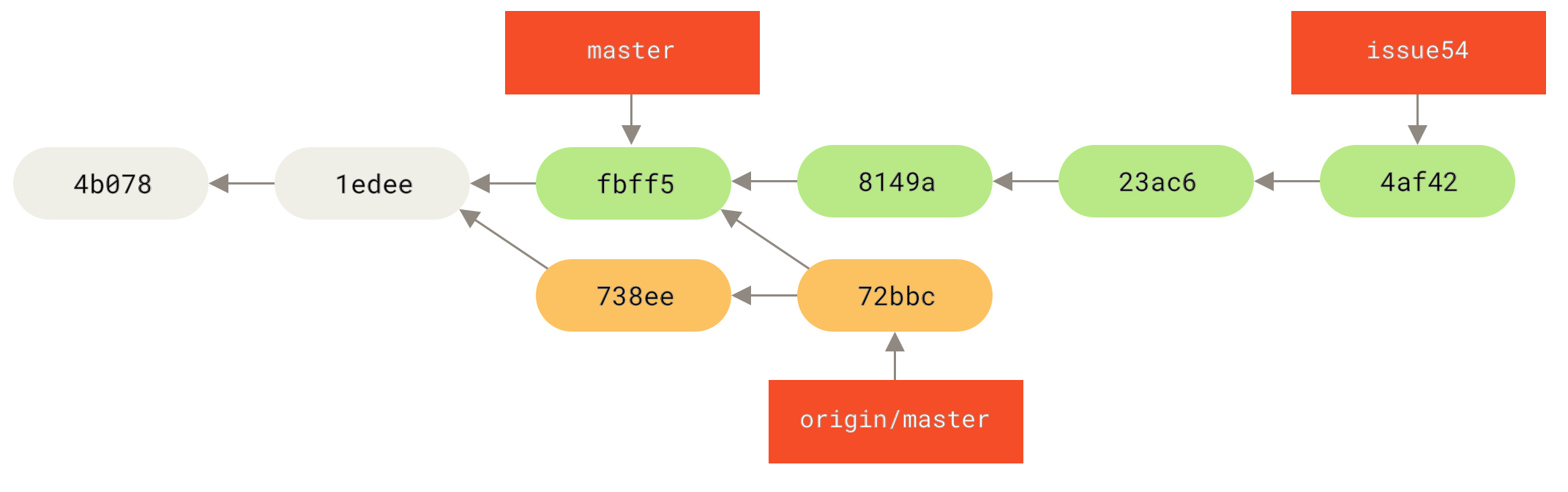

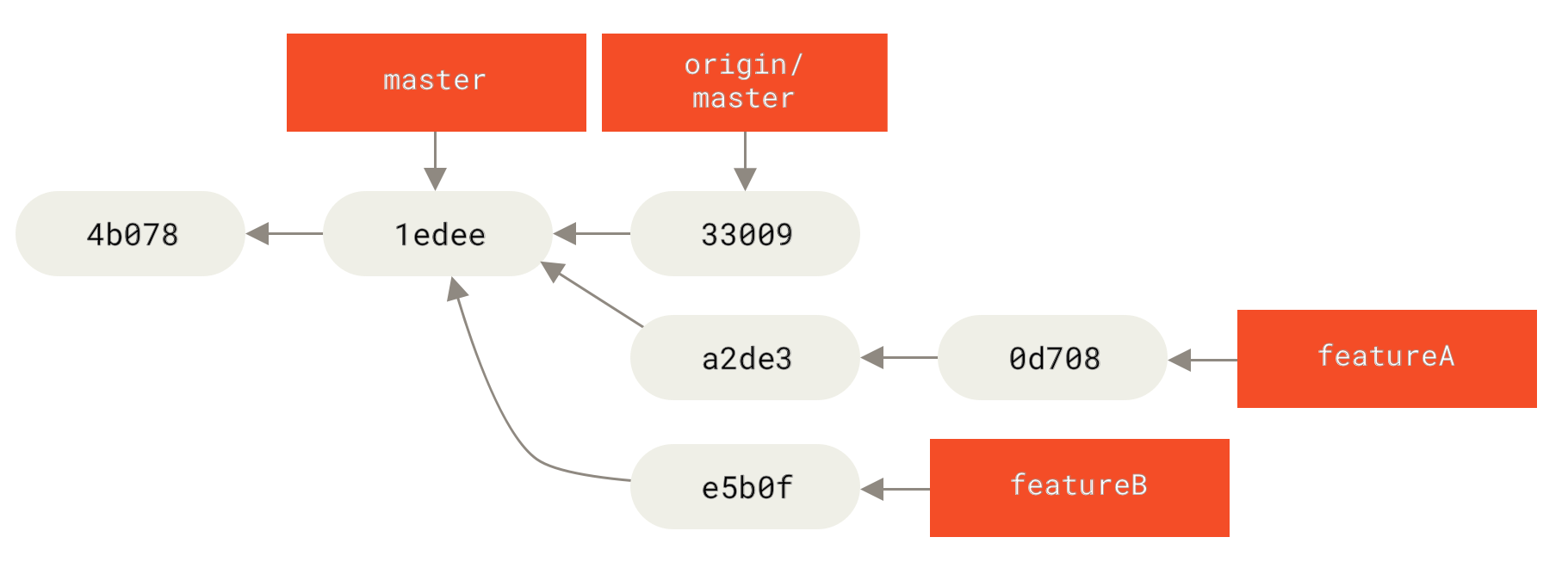

At this point, John’s local repository looks something like this:

Now John can merge Jessica’s work that he fetched into his own local work:

$ git merge origin/master Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy. TODO | 1 + 1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

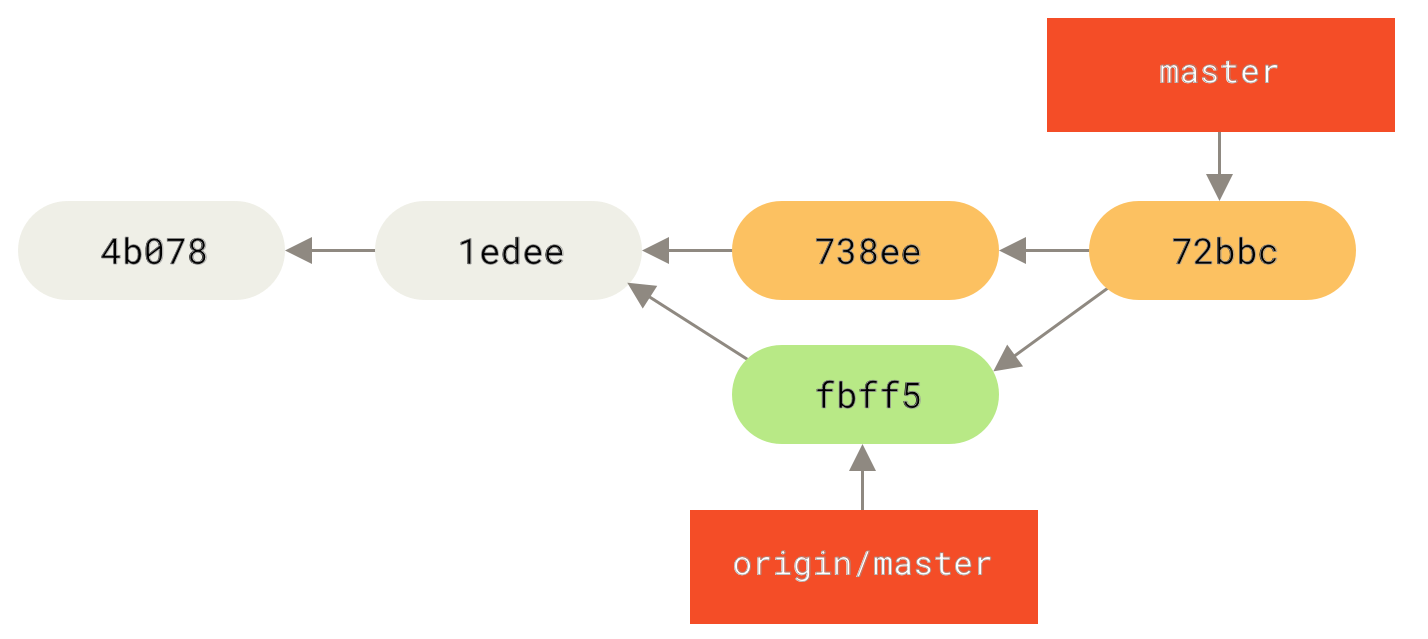

As long as that local merge goes smoothly, John’s updated history will now look like this:

origin/master.At this point, John might want to test this new code to make sure none of Jessica’s work affects any of his and, as long as everything seems fine, he can finally push the new merged work up to the server:

$ git push origin master ... To john@githost:simplegit.git fbff5bc..72bbc59 master -> master

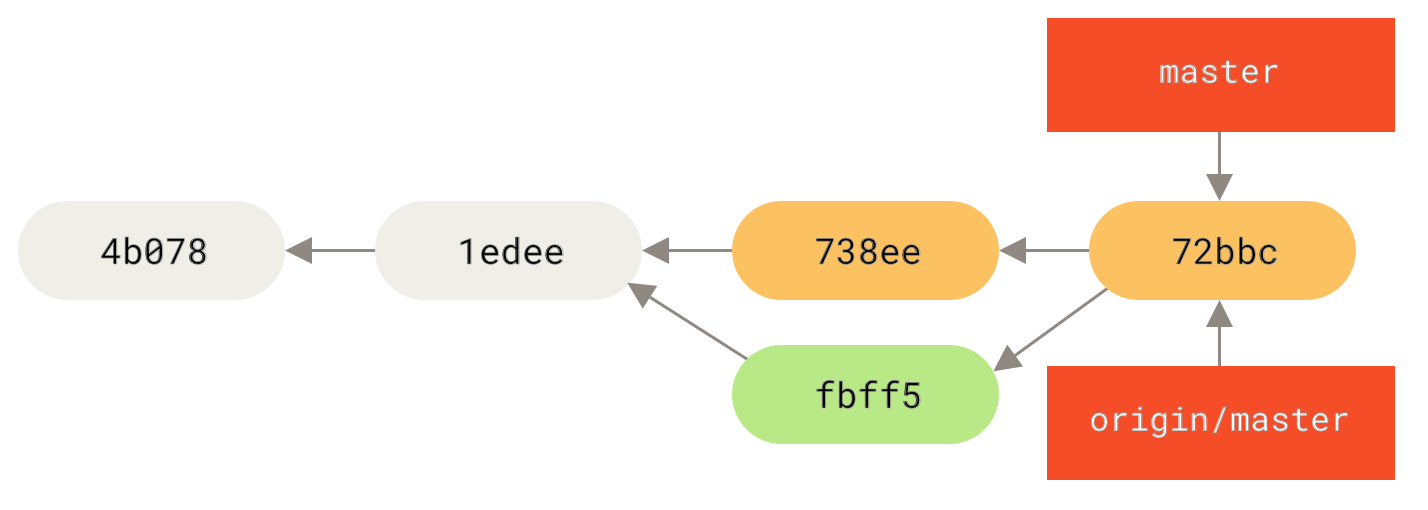

In the end, John’s commit history will look like this:

origin server.In the meantime, Jessica has created a new topic branch called issue54, and made three commits to that branch.

She hasn’t fetched John’s changes yet, so her commit history looks like this:

Suddenly, Jessica learns that John has pushed some new work to the server and she wants to take a look at it, so she can fetch all new content from the server that she does not yet have with:

# Jessica's Machine $ git fetch origin ... From jessica@githost:simplegit fbff5bc..72bbc59 master -> origin/master

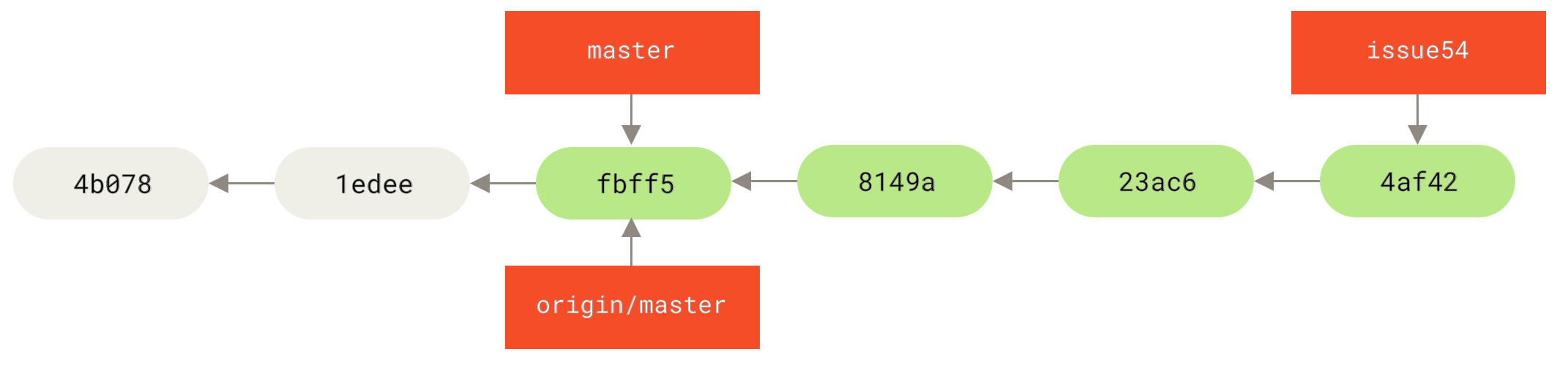

That pulls down the work John has pushed up in the meantime. Jessica’s history now looks like this:

Jessica thinks her topic branch is ready, but she wants to know what part of John’s fetched work she has to merge into her work so that she can push.

She runs git log to find out:

$ git log --no-merges issue54..origin/master commit 738ee872852dfaa9d6634e0dea7a324040193016 Author: John Smith <jsmith@example.com> Date: Fri May 29 16:01:27 2009 -0700 remove invalid default value

The issue54..origin/master syntax is a log filter that asks Git to display only those commits that are on the latter branch (in this case origin/master) that are not on the first branch (in this case issue54).

We’ll go over this syntax in detail in Commit Ranges.

From the above output, we can see that there is a single commit that John has made that Jessica has not merged into her local work.

If she merges origin/master, that is the single commit that will modify her local work.

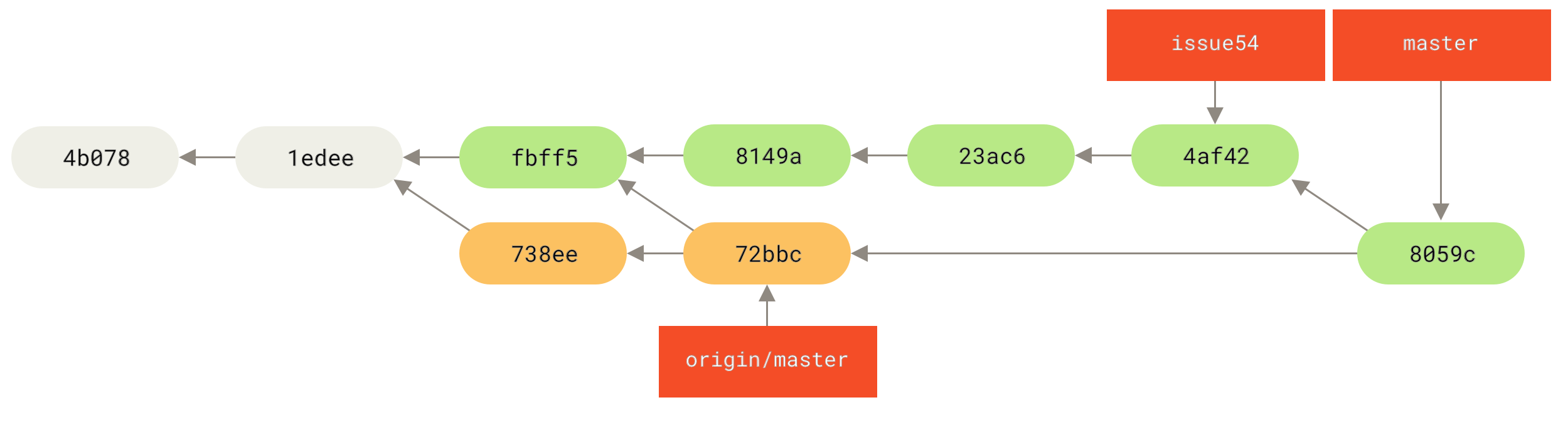

Now, Jessica can merge her topic work into her master branch, merge John’s work (origin/master) into her master branch, and then push back to the server again.

First (having committed all of the work on her issue54 topic branch), Jessica switches back to her master branch in preparation for integrating all this work:

$ git checkout master Switched to branch 'master' Your branch is behind 'origin/master' by 2 commits, and can be fast-forwarded.

Jessica can merge either origin/master or issue54 first — they’re both upstream, so the order doesn’t matter.

The end snapshot should be identical no matter which order she chooses; only the history will be different.

She chooses to merge the issue54 branch first:

$ git merge issue54 Updating fbff5bc..4af4298 Fast forward README | 1 + lib/simplegit.rb | 6 +++++- 2 files changed, 6 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)

No problems occur; as you can see it was a simple fast-forward merge.

Jessica now completes the local merging process by merging John’s earlier fetched work that is sitting in the origin/master branch:

$ git merge origin/master Auto-merging lib/simplegit.rb Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy. lib/simplegit.rb | 2 +- 1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)

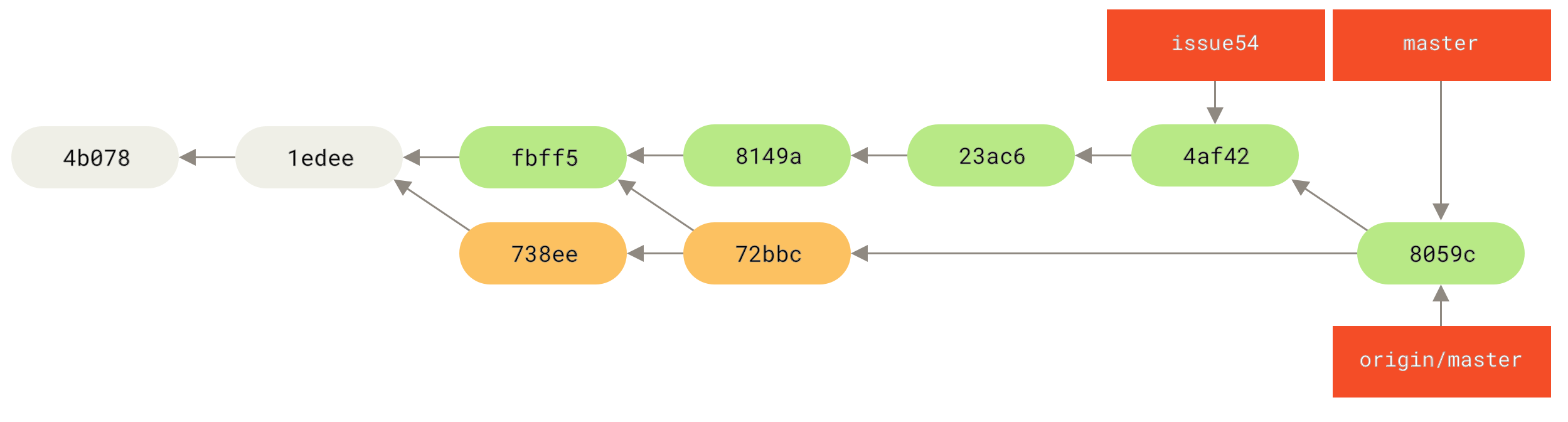

Everything merges cleanly, and Jessica’s history now looks like this:

Now origin/master is reachable from Jessica’s master branch, so she should be able to successfully push (assuming John hasn’t pushed even more changes in the meantime):

$ git push origin master ... To jessica@githost:simplegit.git 72bbc59..8059c15 master -> master

Each developer has committed a few times and merged each other’s work successfully.

That is one of the simplest workflows.

You work for a while (generally in a topic branch), and merge that work into your master branch when it’s ready to be integrated.

When you want to share that work, you fetch and merge your master from origin/master if it has changed, and finally push to the master branch on the server.

The general sequence is something like this:

Private Managed Team

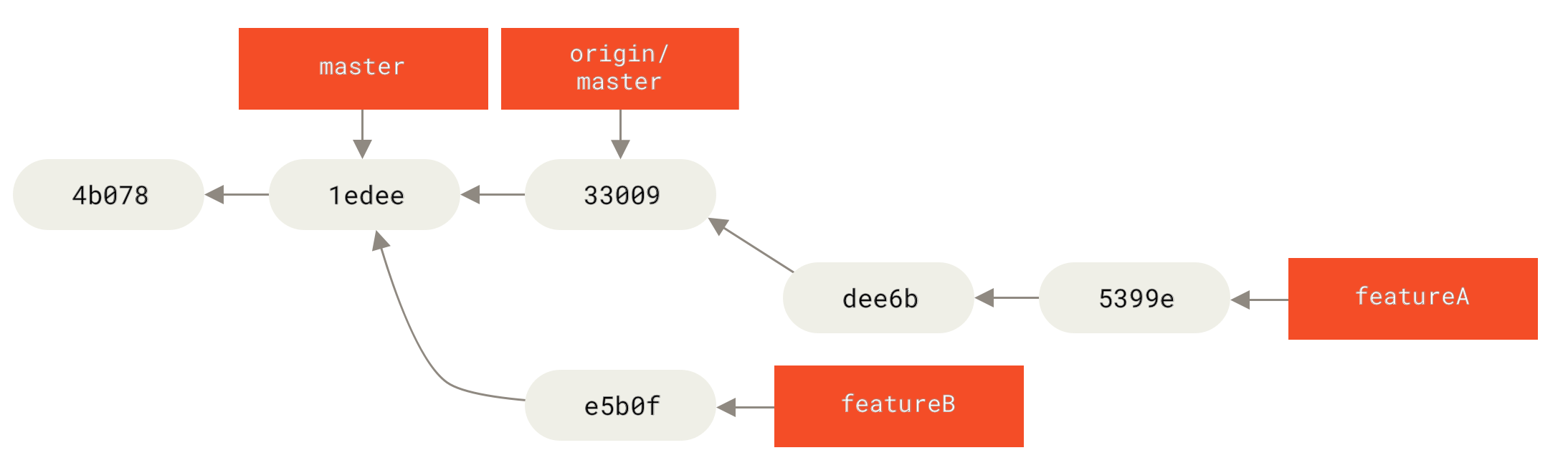

In this next scenario, you’ll look at contributor roles in a larger private group. You’ll learn how to work in an environment where small groups collaborate on features, after which those team-based contributions are integrated by another party.

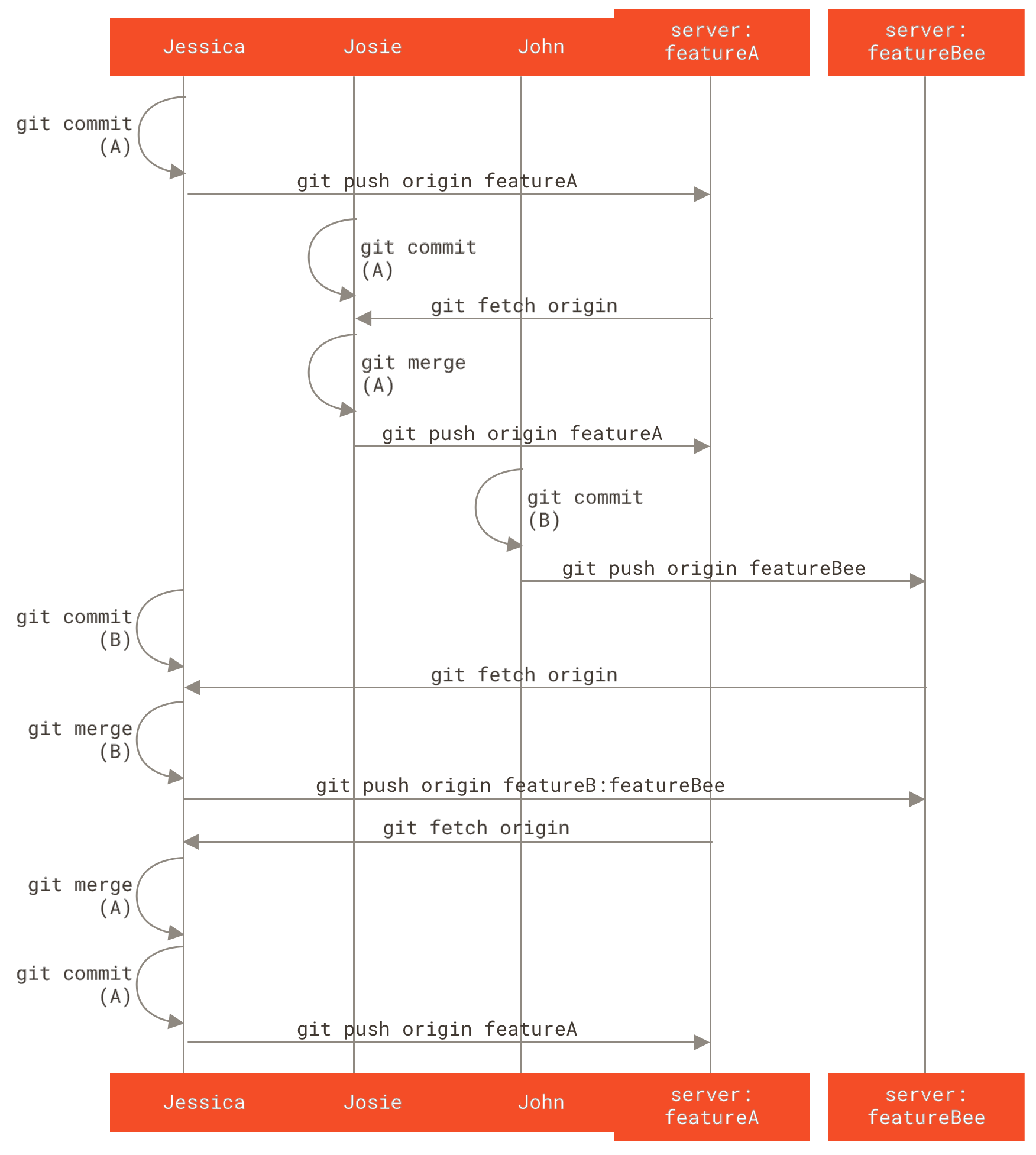

Let’s say that John and Jessica are working together on one feature (call this featureA''), while Jessica and a third developer, Josie, are working on a second (say, featureB'').

In this case, the company is using a type of integration-manager workflow where the work of the individual groups is integrated only by certain engineers, and the master branch of the main repo can be updated only by those engineers.

In this scenario, all work is done in team-based branches and pulled together by the integrators later.

Let’s follow Jessica’s workflow as she works on her two features, collaborating in parallel with two different developers in this environment.

Assuming she already has her repository cloned, she decides to work on featureA first.

She creates a new branch for the feature and does some work on it there:

# Jessica's Machine $ git checkout -b featureA Switched to a new branch 'featureA' $ vim lib/simplegit.rb $ git commit -am 'add limit to log function' [featureA 3300904] add limit to log function 1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)

At this point, she needs to share her work with John, so she pushes her featureA branch commits up to the server.

Jessica doesn’t have push access to the master branch — only the integrators do — so she has to push to another branch in order to collaborate with John:

$ git push -u origin featureA ... To jessica@githost:simplegit.git * [new branch] featureA -> featureA

Jessica emails John to tell him that she’s pushed some work into a branch named featureA and he can look at it now.

While she waits for feedback from John, Jessica decides to start working on featureB with Josie.

To begin, she starts a new feature branch, basing it off the server’s master branch:

# Jessica's Machine $ git fetch origin $ git checkout -b featureB origin/master Switched to a new branch 'featureB'

Now, Jessica makes a couple of commits on the featureB branch:

$ vim lib/simplegit.rb $ git commit -am 'made the ls-tree function recursive' [featureB e5b0fdc] made the ls-tree function recursive 1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-) $ vim lib/simplegit.rb $ git commit -am 'add ls-files' [featureB 8512791] add ls-files 1 files changed, 5 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

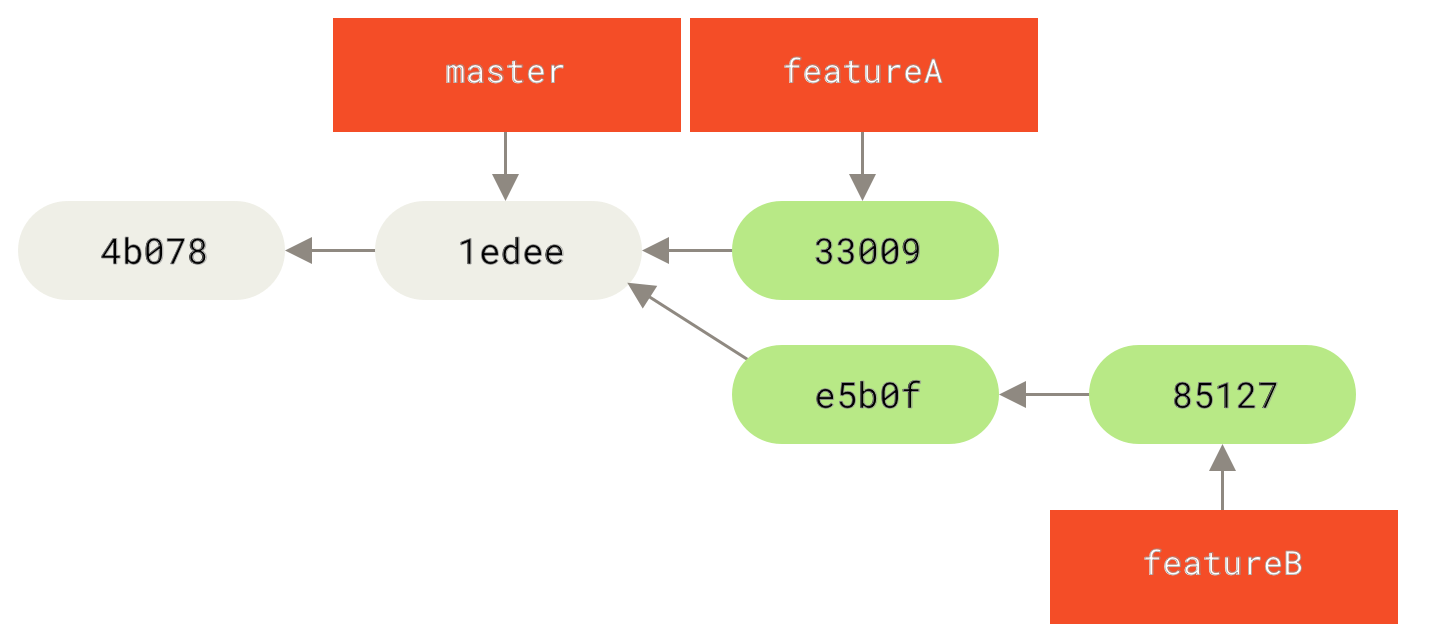

Jessica’s repository now looks like this:

She’s ready to push her work, but gets an email from Josie that a branch with some initial `featureB'' work on it was already pushed to the server as the `featureBee branch.

Jessica needs to merge those changes with her own before she can push her work to the server.

Jessica first fetches Josie’s changes with git fetch:

$ git fetch origin ... From jessica@githost:simplegit * [new branch] featureBee -> origin/featureBee

Assuming Jessica is still on her checked-out featureB branch, she can now merge Josie’s work into that branch with git merge:

$ git merge origin/featureBee Auto-merging lib/simplegit.rb Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy. lib/simplegit.rb | 4 ++++ 1 files changed, 4 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

At this point, Jessica wants to push all of this merged `featureB'' work back to the server, but she doesn’t want to simply push her own `featureB branch.

Rather, since Josie has already started an upstream featureBee branch, Jessica wants to push to that branch, which she does with:

$ git push -u origin featureB:featureBee ... To jessica@githost:simplegit.git fba9af8..cd685d1 featureB -> featureBee

This is called a refspec.

See The Refspec for a more detailed discussion of Git refspecs and different things you can do with them.

Also notice the -u flag; this is short for --set-upstream, which configures the branches for easier pushing and pulling later.

Suddenly, Jessica gets email from John, who tells her he’s pushed some changes to the featureA branch on which they are collaborating, and he asks Jessica to take a look at them.

Again, Jessica runs a simple git fetch to fetch all new content from the server, including (of course) John’s latest work:

$ git fetch origin ... From jessica@githost:simplegit 3300904..aad881d featureA -> origin/featureA

Jessica can display the log of John’s new work by comparing the content of the newly-fetched featureA branch with her local copy of the same branch:

$ git log featureA..origin/featureA

commit aad881d154acdaeb2b6b18ea0e827ed8a6d671e6

Author: John Smith <jsmith@example.com>

Date: Fri May 29 19:57:33 2009 -0700

changed log output to 30 from 25

If Jessica likes what she sees, she can merge John’s new work into her local featureA branch with:

$ git checkout featureA Switched to branch 'featureA' $ git merge origin/featureA Updating 3300904..aad881d Fast forward lib/simplegit.rb | 10 +++++++++- 1 files changed, 9 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)

Finally, Jessica might want to make a couple minor changes to all that merged content, so she is free to make those changes, commit them to her local featureA branch, and push the end result back to the server.

$ git commit -am 'small tweak' [featureA 774b3ed] small tweak 1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-) $ git push ... To jessica@githost:simplegit.git 3300904..774b3ed featureA -> featureA

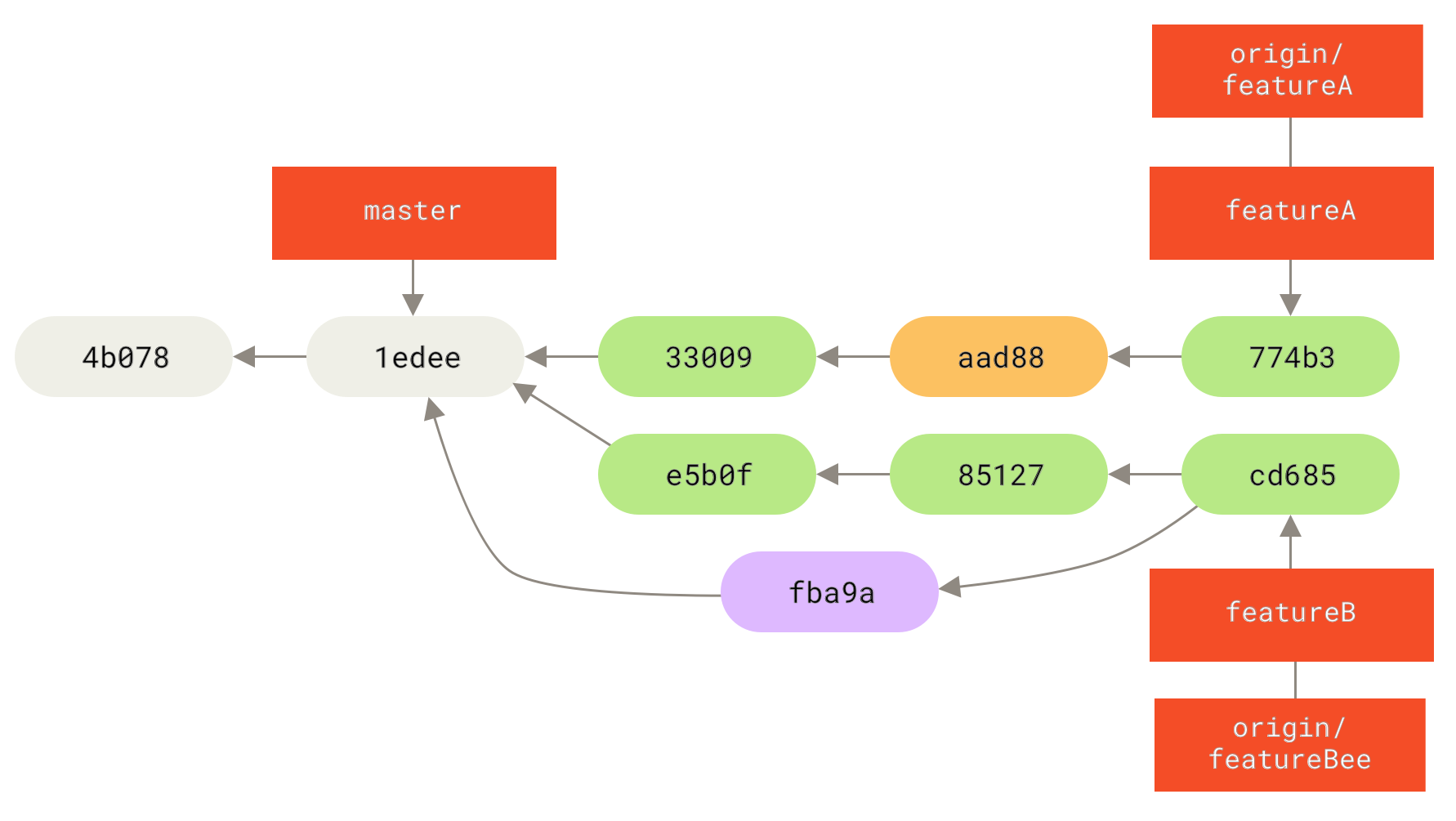

Jessica’s commit history now looks something like this:

At some point, Jessica, Josie, and John inform the integrators that the featureA and featureBee branches on the server are ready for integration into the mainline.

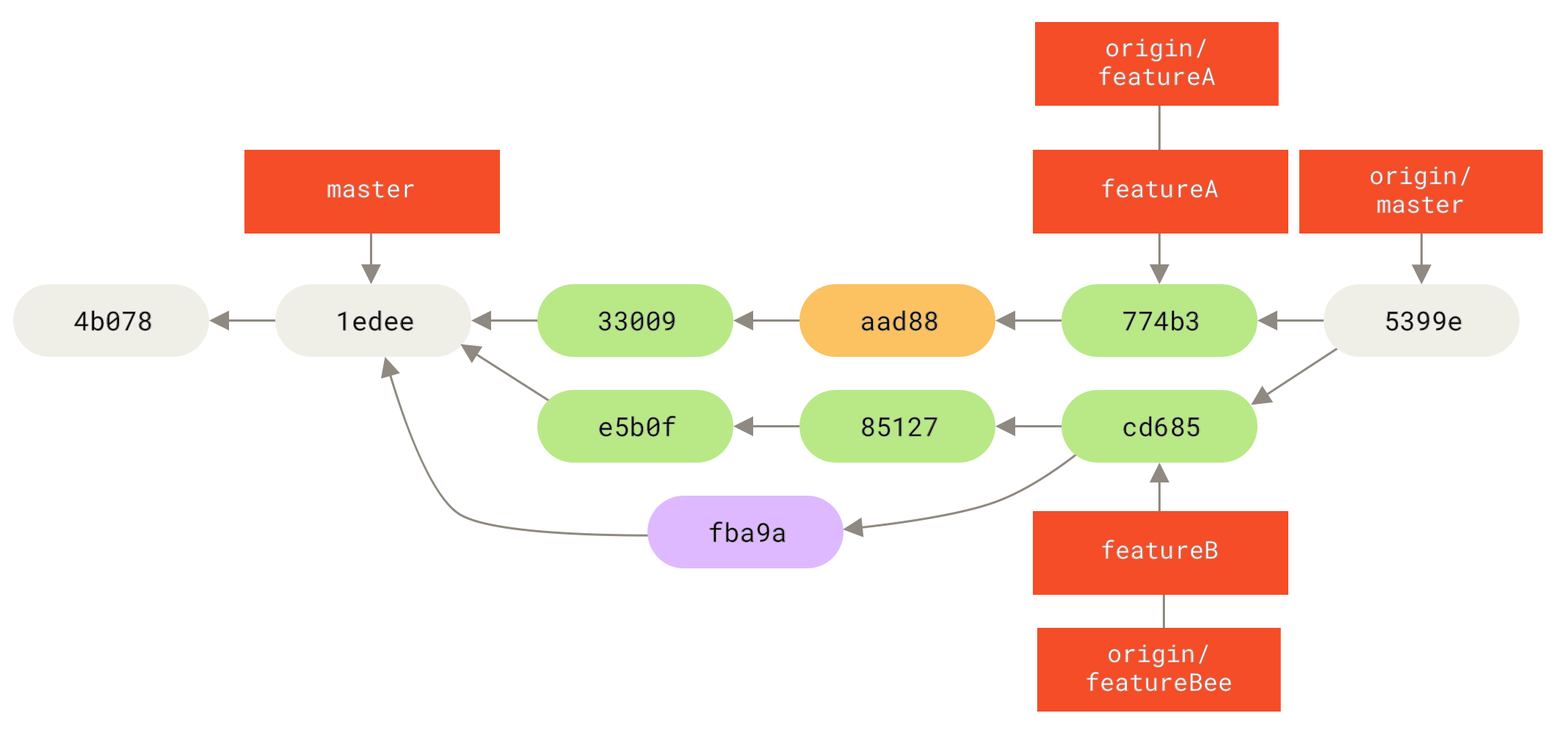

After the integrators merge these branches into the mainline, a fetch will bring down the new merge commit, making the history look like this:

Many groups switch to Git because of this ability to have multiple teams working in parallel, merging the different lines of work late in the process. The ability of smaller subgroups of a team to collaborate via remote branches without necessarily having to involve or impede the entire team is a huge benefit of Git. The sequence for the workflow you saw here is something like this:

Forked Public Project

Contributing to public projects is a bit different. Because you don’t have the permissions to directly update branches on the project, you have to get the work to the maintainers some other way. This first example describes contributing via forking on Git hosts that support easy forking. Many hosting sites support this (including GitHub, BitBucket, repo.or.cz, and others), and many project maintainers expect this style of contribution. The next section deals with projects that prefer to accept contributed patches via email.

First, you’ll probably want to clone the main repository, create a topic branch for the patch or patch series you’re planning to contribute, and do your work there. The sequence looks basically like this:

$ git clone <url> $ cd project $ git checkout -b featureA ... work ... $ git commit ... work ... $ git commit

You may want to use rebase -i to squash your work down to a single commit, or rearrange the work in the commits to make the patch easier for the maintainer to review — see Rewriting History for more information about interactive rebasing.

When your branch work is finished and you’re ready to contribute it back to the maintainers, go to the original project page and click the `Fork'' button, creating your own writable fork of the project.

You then need to add this repository URL as a new remote of your local repository; in this example, let’s call it `myfork:

$ git remote add myfork <url>

You then need to push your new work to this repository.

It’s easiest to push the topic branch you’re working on to your forked repository, rather than merging that work into your master branch and pushing that.

The reason is that if your work isn’t accepted or is cherry-picked, you don’t have to rewind your master branch (the Git cherry-pick operation is covered in more detail in Rebasing and Cherry-Picking Workflows).

If the maintainers merge, rebase, or cherry-pick your work, you’ll eventually get it back via pulling from their repository anyhow.

In any event, you can push your work with:

$ git push -u myfork featureA

Once your work has been pushed to your fork of the repository, you need to notify the maintainers of the original project that you have work you’d like them to merge.

This is often called a pull request, and you typically generate such a request either via the website — GitHub has its own `Pull Request'' mechanism that we’ll go over in GitHub — or you can run the `git request-pull command and email the subsequent output to the project maintainer manually.

The git request-pull command takes the base branch into which you want your topic branch pulled and the Git repository URL you want them to pull from, and produces a summary of all the changes you’re asking to be pulled.

For instance, if Jessica wants to send John a pull request, and she’s done two commits on the topic branch she just pushed, she can run this:

$ git request-pull origin/master myfork

The following changes since commit 1edee6b1d61823a2de3b09c160d7080b8d1b3a40:

Jessica Smith (1):

added a new function

are available in the git repository at:

git://githost/simplegit.git featureA

Jessica Smith (2):

add limit to log function

change log output to 30 from 25

lib/simplegit.rb | 10 +++++++++-

1 files changed, 9 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)

This output can be sent to the maintainer — it tells them where the work was branched from, summarizes the commits, and identifies from where the new work is to be pulled.

On a project for which you’re not the maintainer, it’s generally easier to have a branch like master always track origin/master and to do your work in topic branches that you can easily discard if they’re rejected.

Having work themes isolated into topic branches also makes it easier for you to rebase your work if the tip of the main repository has moved in the meantime and your commits no longer apply cleanly.

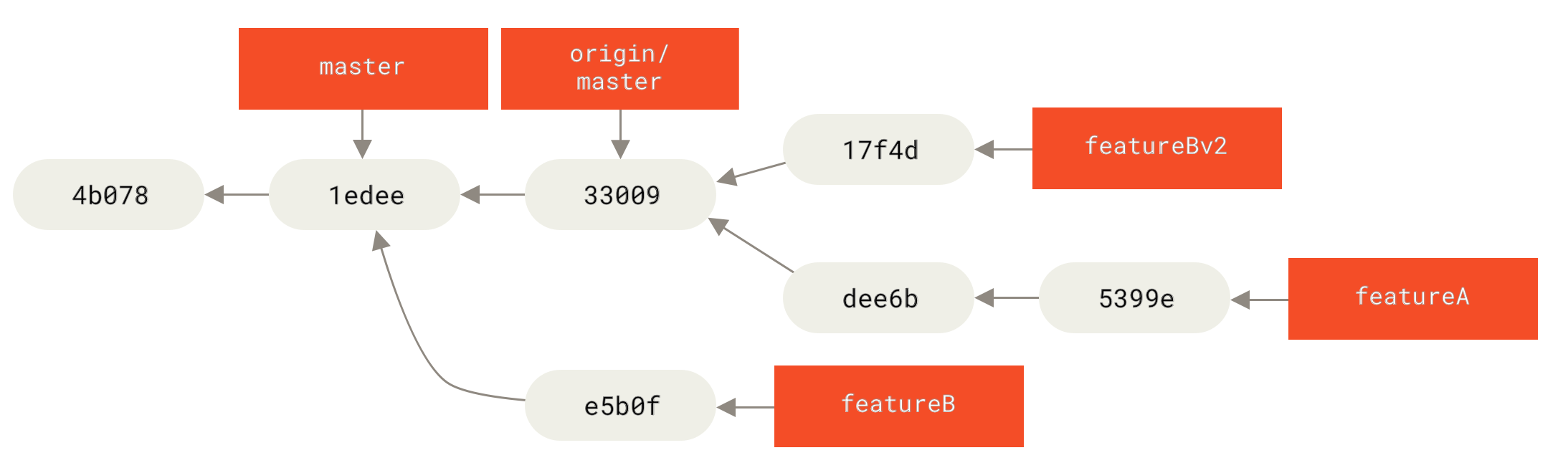

For example, if you want to submit a second topic of work to the project, don’t continue working on the topic branch you just pushed up — start over from the main repository’s master branch:

$ git checkout -b featureB origin/master ... work ... $ git commit $ git push myfork featureB $ git request-pull origin/master myfork ... email generated request pull to maintainer ... $ git fetch origin

Now, each of your topics is contained within a silo — similar to a patch queue — that you can rewrite, rebase, and modify without the topics interfering or interdepending on each other, like so:

featureB work.Let’s say the project maintainer has pulled in a bunch of other patches and tried your first branch, but it no longer cleanly merges.

In this case, you can try to rebase that branch on top of origin/master, resolve the conflicts for the maintainer, and then resubmit your changes:

$ git checkout featureA $ git rebase origin/master $ git push -f myfork featureA

This rewrites your history to now look like Commit history after featureA work..

featureA work.Because you rebased the branch, you have to specify the -f to your push command in order to be able to replace the featureA branch on the server with a commit that isn’t a descendant of it.

An alternative would be to push this new work to a different branch on the server (perhaps called featureAv2).

Let’s look at one more possible scenario: the maintainer has looked at work in your second branch and likes the concept but would like you to change an implementation detail.

You’ll also take this opportunity to move the work to be based off the project’s current master branch.

You start a new branch based off the current origin/master branch, squash the featureB changes there, resolve any conflicts, make the implementation change, and then push that as a new branch:

$ git checkout -b featureBv2 origin/master $ git merge --squash featureB ... change implementation ... $ git commit $ git push myfork featureBv2

The --squash option takes all the work on the merged branch and squashes it into one changeset producing the repository state as if a real merge happened, without actually making a merge commit.

This means your future commit will have one parent only and allows you to introduce all the changes from another branch and then make more changes before recording the new commit.

Also the --no-commit option can be useful to delay the merge commit in case of the default merge process.

At this point, you can notify the maintainer that you’ve made the requested changes, and that they can find those changes in your featureBv2 branch.

featureBv2 work.Public Project over Email

Many projects have established procedures for accepting patches — you’ll need to check the specific rules for each project, because they will differ. Since there are several older, larger projects which accept patches via a developer mailing list, we’ll go over an example of that now.

The workflow is similar to the previous use case — you create topic branches for each patch series you work on. The difference is how you submit them to the project. Instead of forking the project and pushing to your own writable version, you generate email versions of each commit series and email them to the developer mailing list:

$ git checkout -b topicA ... work ... $ git commit ... work ... $ git commit

Now you have two commits that you want to send to the mailing list.

You use git format-patch to generate the mbox-formatted files that you can email to the list — it turns each commit into an email message with the first line of the commit message as the subject and the rest of the message plus the patch that the commit introduces as the body.

The nice thing about this is that applying a patch from an email generated with format-patch preserves all the commit information properly.

$ git format-patch -M origin/master 0001-add-limit-to-log-function.patch 0002-changed-log-output-to-30-from-25.patch

The format-patch command prints out the names of the patch files it creates.

The -M switch tells Git to look for renames.

The files end up looking like this:

$ cat 0001-add-limit-to-log-function.patch

From 330090432754092d704da8e76ca5c05c198e71a8 Mon Sep 17 00:00:00 2001

From: Jessica Smith <jessica@example.com>

Date: Sun, 6 Apr 2008 10:17:23 -0700

Subject: [PATCH 1/2] add limit to log function

Limit log functionality to the first 20

---

lib/simplegit.rb | 2 +-

1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)

diff --git a/lib/simplegit.rb b/lib/simplegit.rb

index 76f47bc..f9815f1 100644

--- a/lib/simplegit.rb

+++ b/lib/simplegit.rb

@@ -14,7 +14,7 @@ class SimpleGit

end

def log(treeish = 'master')

- command("git log #{treeish}")

+ command("git log -n 20 #{treeish}")

end

def ls_tree(treeish = 'master')

--

2.1.0

You can also edit these patch files to add more information for the email list that you don’t want to show up in the commit message.

If you add text between the --- line and the beginning of the patch (the diff --git line), the developers can read it, but that content is ignored by the patching process.

To email this to a mailing list, you can either paste the file into your email program or send it via a command-line program.

Pasting the text often causes formatting issues, especially with `smarter'' clients that don’t preserve newlines and other whitespace appropriately.

Luckily, Git provides a tool to help you send properly formatted patches via IMAP, which may be easier for you.

We’ll demonstrate how to send a patch via Gmail, which happens to be the email agent we know best; you can read detailed instructions for a number of mail programs at the end of the aforementioned `Documentation/SubmittingPatches file in the Git source code.

First, you need to set up the imap section in your ~/.gitconfig file.

You can set each value separately with a series of git config commands, or you can add them manually, but in the end your config file should look something like this:

[imap] folder = "[Gmail]/Drafts" host = imaps://imap.gmail.com user = user@gmail.com pass = YX]8g76G_2^sFbd port = 993 sslverify = false

If your IMAP server doesn’t use SSL, the last two lines probably aren’t necessary, and the host value will be imap:// instead of imaps://.

When that is set up, you can use git imap-send to place the patch series in the Drafts folder of the specified IMAP server:

$ cat *.patch |git imap-send Resolving imap.gmail.com... ok Connecting to [74.125.142.109]:993... ok Logging in... sending 2 messages 100% (2/2) done

At this point, you should be able to go to your Drafts folder, change the To field to the mailing list you’re sending the patch to, possibly CC the maintainer or person responsible for that section, and send it off.

You can also send the patches through an SMTP server.

As before, you can set each value separately with a series of git config commands, or you can add them manually in the sendemail section in your ~/.gitconfig file:

[sendemail] smtpencryption = tls smtpserver = smtp.gmail.com smtpuser = user@gmail.com smtpserverport = 587

After this is done, you can use git send-email to send your patches:

$ git send-email *.patch 0001-added-limit-to-log-function.patch 0002-changed-log-output-to-30-from-25.patch Who should the emails appear to be from? [Jessica Smith <jessica@example.com>] Emails will be sent from: Jessica Smith <jessica@example.com> Who should the emails be sent to? jessica@example.com Message-ID to be used as In-Reply-To for the first email? y

Then, Git spits out a bunch of log information looking something like this for each patch you’re sending:

(mbox) Adding cc: Jessica Smith <jessica@example.com> from \line 'From: Jessica Smith <jessica@example.com>' OK. Log says: Sendmail: /usr/sbin/sendmail -i jessica@example.com From: Jessica Smith <jessica@example.com> To: jessica@example.com Subject: [PATCH 1/2] added limit to log function Date: Sat, 30 May 2009 13:29:15 -0700 Message-Id: <1243715356-61726-1-git-send-email-jessica@example.com> X-Mailer: git-send-email 1.6.2.rc1.20.g8c5b.dirty In-Reply-To: <y> References: <y> Result: OK

Summary

This section has covered a number of common workflows for dealing with several very different types of Git projects you’re likely to encounter, and introduced a couple of new tools to help you manage this process. Next, you’ll see how to work the other side of the coin: maintaining a Git project. You’ll learn how to be a benevolent dictator or integration manager.

Maintaining a Project

In addition to knowing how to contribute effectively to a project, you’ll likely need to know how to maintain one.

This can consist of accepting and applying patches generated via format-patch and emailed to you, or integrating changes in remote branches for repositories you’ve added as remotes to your project.

Whether you maintain a canonical repository or want to help by verifying or approving patches, you need to know how to accept work in a way that is clearest for other contributors and sustainable by you over the long run.

Working in Topic Branches

When you’re thinking of integrating new work, it’s generally a good idea to try it out in a topic branch — a temporary branch specifically made to try out that new work.

This way, it’s easy to tweak a patch individually and leave it if it’s not working until you have time to come back to it.

If you create a simple branch name based on the theme of the work you’re going to try, such as ruby_client or something similarly descriptive, you can easily remember it if you have to abandon it for a while and come back later.

The maintainer of the Git project tends to namespace these branches as well — such as sc/ruby_client, where sc is short for the person who contributed the work.

As you’ll remember, you can create the branch based off your master branch like this:

$ git branch sc/ruby_client master

Or, if you want to also switch to it immediately, you can use the checkout -b option:

$ git checkout -b sc/ruby_client master

Now you’re ready to add the contributed work that you received into this topic branch and determine if you want to merge it into your longer-term branches.

Applying Patches from Email

If you receive a patch over email that you need to integrate into your project, you need to apply the patch in your topic branch to evaluate it.

There are two ways to apply an emailed patch: with git apply or with git am.

Applying a Patch with apply

If you received the patch from someone who generated it with git diff or some variation of the Unix diff command (which is not recommended; see the next section), you can apply it with the git apply command.

Assuming you saved the patch at /tmp/patch-ruby-client.patch, you can apply the patch like this:

$ git apply /tmp/patch-ruby-client.patch

This modifies the files in your working directory.

It’s almost identical to running a patch -p1 command to apply the patch, although it’s more paranoid and accepts fewer fuzzy matches than patch.

It also handles file adds, deletes, and renames if they’re described in the git diff format, which patch won’t do.

Finally, git apply is an `apply all or abort all'' model where either everything is applied or nothing is, whereas `patch can partially apply patchfiles, leaving your working directory in a weird state.

git apply is overall much more conservative than patch.

It won’t create a commit for you — after running it, you must stage and commit the changes introduced manually.

You can also use git apply to see if a patch applies cleanly before you try actually applying it — you can run git apply --check with the patch:

$ git apply --check 0001-seeing-if-this-helps-the-gem.patch error: patch failed: ticgit.gemspec:1 error: ticgit.gemspec: patch does not apply

If there is no output, then the patch should apply cleanly. This command also exits with a non-zero status if the check fails, so you can use it in scripts if you want.

Applying a Patch with am

If the contributor is a Git user and was good enough to use the format-patch command to generate their patch, then your job is easier because the patch contains author information and a commit message for you.

If you can, encourage your contributors to use format-patch instead of diff to generate patches for you.

You should only have to use git apply for legacy patches and things like that.

To apply a patch generated by format-patch, you use git am (the command is named am as it is used to "apply a series of patches from a mailbox").

Technically, git am is built to read an mbox file, which is a simple, plain-text format for storing one or more email messages in one text file.

It looks something like this:

From 330090432754092d704da8e76ca5c05c198e71a8 Mon Sep 17 00:00:00 2001 From: Jessica Smith <jessica@example.com> Date: Sun, 6 Apr 2008 10:17:23 -0700 Subject: [PATCH 1/2] add limit to log function Limit log functionality to the first 20

This is the beginning of the output of the git format-patch command that you saw in the previous section; it also represents a valid mbox email format.

If someone has emailed you the patch properly using git send-email, and you download that into an mbox format, then you can point git am to that mbox file, and it will start applying all the patches it sees.

If you run a mail client that can save several emails out in mbox format, you can save entire patch series into a file and then use git am to apply them one at a time.

However, if someone uploaded a patch file generated via git format-patch to a ticketing system or something similar, you can save the file locally and then pass that file saved on your disk to git am to apply it:

$ git am 0001-limit-log-function.patch Applying: add limit to log function

You can see that it applied cleanly and automatically created the new commit for you.

The author information is taken from the email’s From and Date headers, and the message of the commit is taken from the Subject and body (before the patch) of the email.

For example, if this patch was applied from the mbox example above, the commit generated would look something like this:

$ git log --pretty=fuller -1 commit 6c5e70b984a60b3cecd395edd5b48a7575bf58e0 Author: Jessica Smith <jessica@example.com> AuthorDate: Sun Apr 6 10:17:23 2008 -0700 Commit: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com> CommitDate: Thu Apr 9 09:19:06 2009 -0700 add limit to log function Limit log functionality to the first 20

The Commit information indicates the person who applied the patch and the time it was applied.

The Author information is the individual who originally created the patch and when it was originally created.

But it’s possible that the patch won’t apply cleanly.

Perhaps your main branch has diverged too far from the branch the patch was built from, or the patch depends on another patch you haven’t applied yet.

In that case, the git am process will fail and ask you what you want to do:

$ git am 0001-seeing-if-this-helps-the-gem.patch Applying: seeing if this helps the gem error: patch failed: ticgit.gemspec:1 error: ticgit.gemspec: patch does not apply Patch failed at 0001. When you have resolved this problem run "git am --resolved". If you would prefer to skip this patch, instead run "git am --skip". To restore the original branch and stop patching run "git am --abort".

This command puts conflict markers in any files it has issues with, much like a conflicted merge or rebase operation.

You solve this issue much the same way — edit the file to resolve the conflict, stage the new file, and then run git am --resolved to continue to the next patch:

$ (fix the file) $ git add ticgit.gemspec $ git am --resolved Applying: seeing if this helps the gem

If you want Git to try a bit more intelligently to resolve the conflict, you can pass a -3 option to it, which makes Git attempt a three-way merge.

This option isn’t on by default because it doesn’t work if the commit the patch says it was based on isn’t in your repository.

If you do have that commit — if the patch was based on a public commit — then the -3 option is generally much smarter about applying a conflicting patch:

$ git am -3 0001-seeing-if-this-helps-the-gem.patch Applying: seeing if this helps the gem error: patch failed: ticgit.gemspec:1 error: ticgit.gemspec: patch does not apply Using index info to reconstruct a base tree... Falling back to patching base and 3-way merge... No changes -- Patch already applied.

In this case, without the -3 option the patch would have been considered as a conflict.

Since the -3 option was used the patch applied cleanly.

If you’re applying a number of patches from an mbox, you can also run the am command in interactive mode, which stops at each patch it finds and asks if you want to apply it:

$ git am -3 -i mbox Commit Body is: -------------------------- seeing if this helps the gem -------------------------- Apply? [y]es/[n]o/[e]dit/[v]iew patch/[a]ccept all

This is nice if you have a number of patches saved, because you can view the patch first if you don’t remember what it is, or not apply the patch if you’ve already done so.

When all the patches for your topic are applied and committed into your branch, you can choose whether and how to integrate them into a longer-running branch.

Checking Out Remote Branches

If your contribution came from a Git user who set up their own repository, pushed a number of changes into it, and then sent you the URL to the repository and the name of the remote branch the changes are in, you can add them as a remote and do merges locally.

For instance, if Jessica sends you an email saying that she has a great new feature in the ruby-client branch of her repository, you can test it by adding the remote and checking out that branch locally:

$ git remote add jessica git://github.com/jessica/myproject.git $ git fetch jessica $ git checkout -b rubyclient jessica/ruby-client

If she emails you again later with another branch containing another great feature, you could directly fetch and checkout because you already have the remote setup.

This is most useful if you’re working with a person consistently. If someone only has a single patch to contribute once in a while, then accepting it over email may be less time consuming than requiring everyone to run their own server and having to continually add and remove remotes to get a few patches. You’re also unlikely to want to have hundreds of remotes, each for someone who contributes only a patch or two. However, scripts and hosted services may make this easier — it depends largely on how you develop and how your contributors develop.

The other advantage of this approach is that you get the history of the commits as well.

Although you may have legitimate merge issues, you know where in your history their work is based; a proper three-way merge is the default rather than having to supply a -3 and hope the patch was generated off a public commit to which you have access.

If you aren’t working with a person consistently but still want to pull from them in this way, you can provide the URL of the remote repository to the git pull command.

This does a one-time pull and doesn’t save the URL as a remote reference:

$ git pull https://github.com/onetimeguy/project From https://github.com/onetimeguy/project * branch HEAD -> FETCH_HEAD Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

Determining What Is Introduced

Now you have a topic branch that contains contributed work. At this point, you can determine what you’d like to do with it. This section revisits a couple of commands so you can see how you can use them to review exactly what you’ll be introducing if you merge this into your main branch.

It’s often helpful to get a review of all the commits that are in this branch but that aren’t in your master branch.

You can exclude commits in the master branch by adding the --not option before the branch name.

This does the same thing as the master..contrib format that we used earlier.

For example, if your contributor sends you two patches and you create a branch called contrib and applied those patches there, you can run this:

$ git log contrib --not master

commit 5b6235bd297351589efc4d73316f0a68d484f118

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Fri Oct 24 09:53:59 2008 -0700

seeing if this helps the gem

commit 7482e0d16d04bea79d0dba8988cc78df655f16a0

Author: Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Oct 22 19:38:36 2008 -0700

updated the gemspec to hopefully work better

To see what changes each commit introduces, remember that you can pass the -p option to git log and it will append the diff introduced to each commit.

To see a full diff of what would happen if you were to merge this topic branch with another branch, you may have to use a weird trick to get the correct results. You may think to run this:

$ git diff master

This command gives you a diff, but it may be misleading.

If your master branch has moved forward since you created the topic branch from it, then you’ll get seemingly strange results.

This happens because Git directly compares the snapshots of the last commit of the topic branch you’re on and the snapshot of the last commit on the master branch.

For example, if you’ve added a line in a file on the master branch, a direct comparison of the snapshots will look like the topic branch is going to remove that line.

If master is a direct ancestor of your topic branch, this isn’t a problem; but if the two histories have diverged, the diff will look like you’re adding all the new stuff in your topic branch and removing everything unique to the master branch.

What you really want to see are the changes added to the topic branch — the work you’ll introduce if you merge this branch with master.

You do that by having Git compare the last commit on your topic branch with the first common ancestor it has with the master branch.

Technically, you can do that by explicitly figuring out the common ancestor and then running your diff on it:

$ git merge-base contrib master 36c7dba2c95e6bbb78dfa822519ecfec6e1ca649 $ git diff 36c7db

or, more concisely:

$ git diff $(git merge-base contrib master)

However, neither of those is particularly convenient, so Git provides another shorthand for doing the same thing: the triple-dot syntax.

In the context of the git diff command, you can put three periods after another branch to do a diff between the last commit of the branch you’re on and its common ancestor with another branch:

$ git diff master...contrib

This command shows you only the work your current topic branch has introduced since its common ancestor with master.

That is a very useful syntax to remember.

Integrating Contributed Work

When all the work in your topic branch is ready to be integrated into a more mainline branch, the question is how to do it. Furthermore, what overall workflow do you want to use to maintain your project? You have a number of choices, so we’ll cover a few of them.

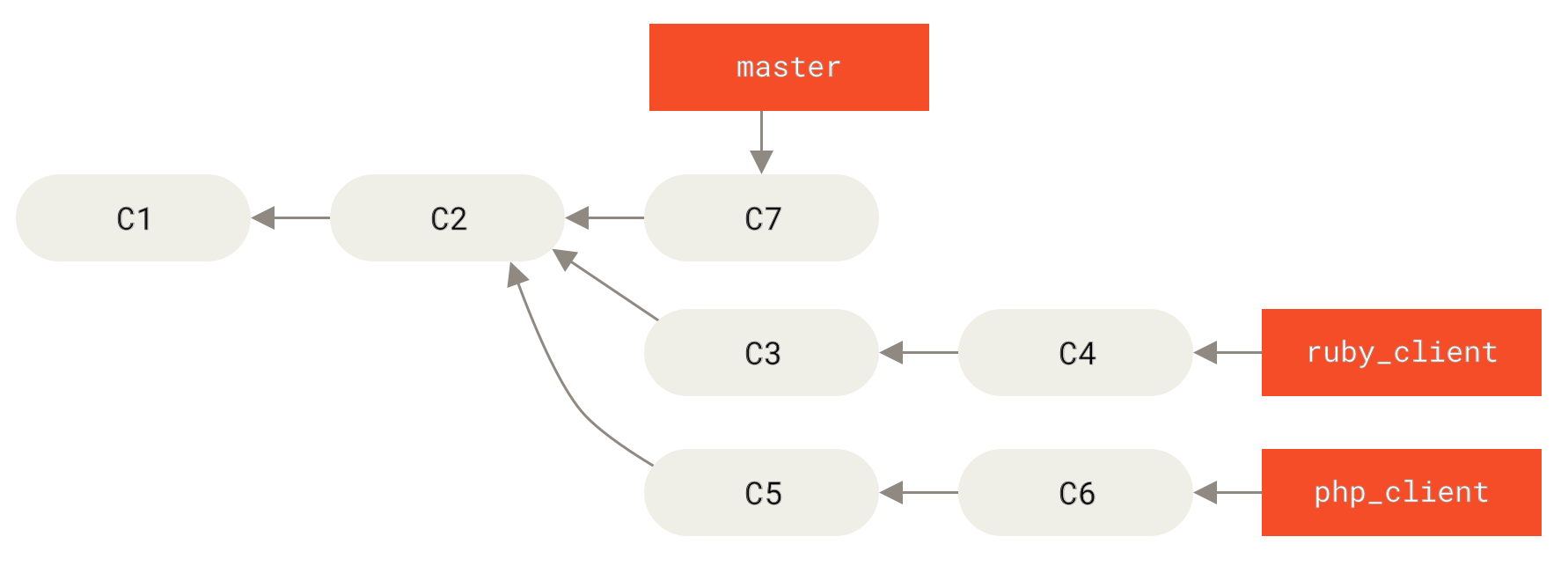

Merging Workflows

One basic workflow is to simply merge all that work directly into your master branch.

In this scenario, you have a master branch that contains basically stable code.

When you have work in a topic branch that you think you’ve completed, or work that someone else has contributed and you’ve verified, you merge it into your master branch, delete that just-merged topic branch, and repeat.

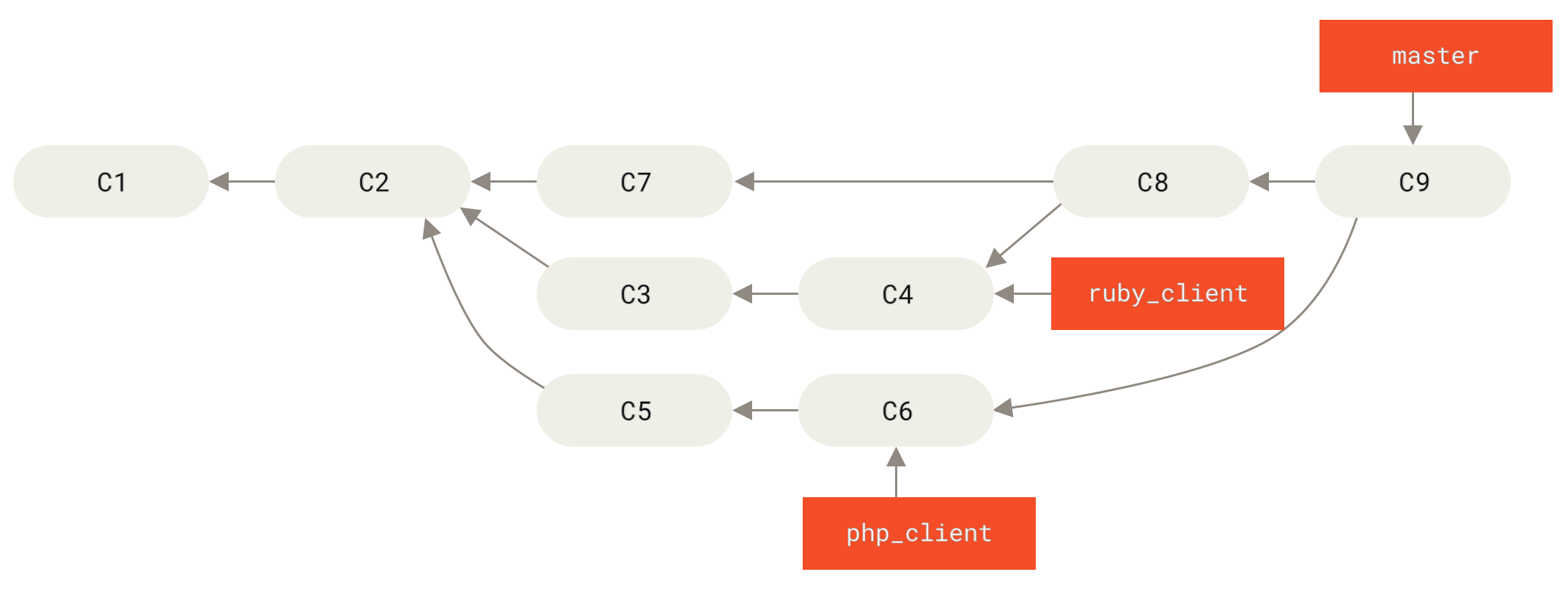

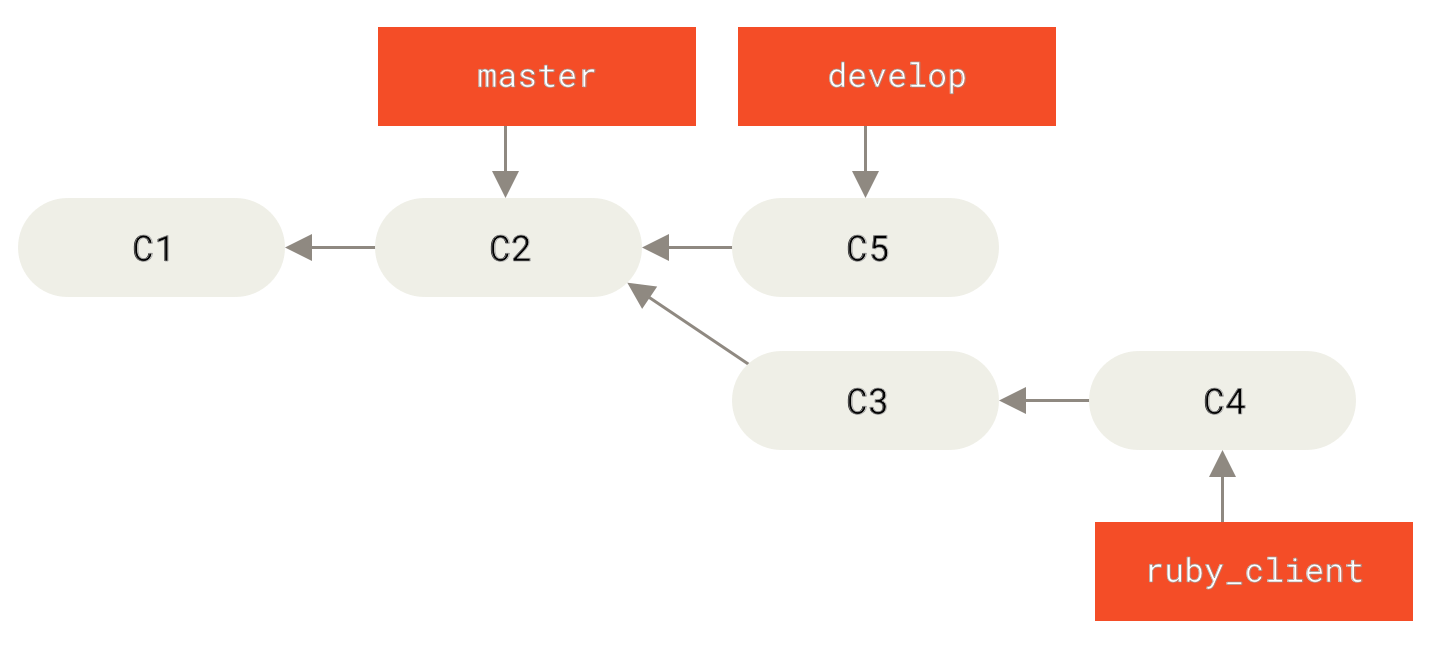

For instance, if we have a repository with work in two branches named ruby_client and php_client that looks like History with several topic branches., and we merge ruby_client followed by php_client, your history will end up looking like After a topic branch merge..

That is probably the simplest workflow, but it can possibly be problematic if you’re dealing with larger or more stable projects where you want to be really careful about what you introduce.

If you have a more important project, you might want to use a two-phase merge cycle.

In this scenario, you have two long-running branches, master and develop, in which you determine that master is updated only when a very stable release is cut and all new code is integrated into the develop branch.

You regularly push both of these branches to the public repository.

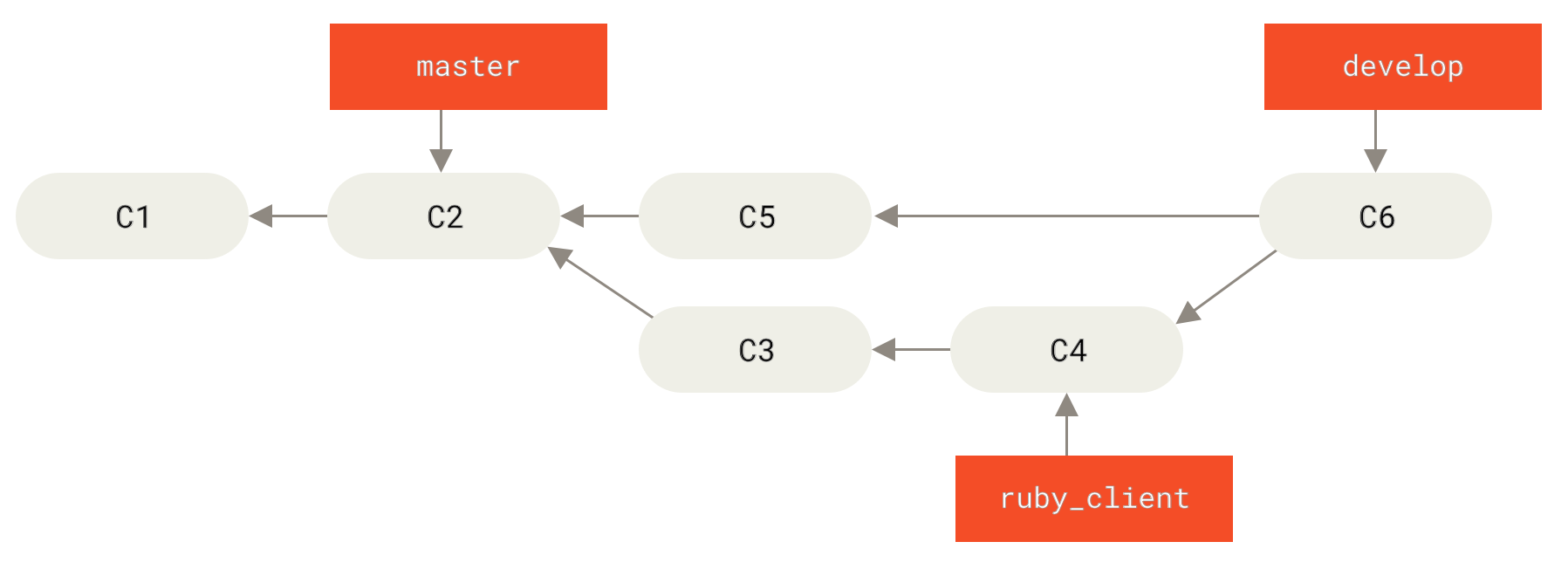

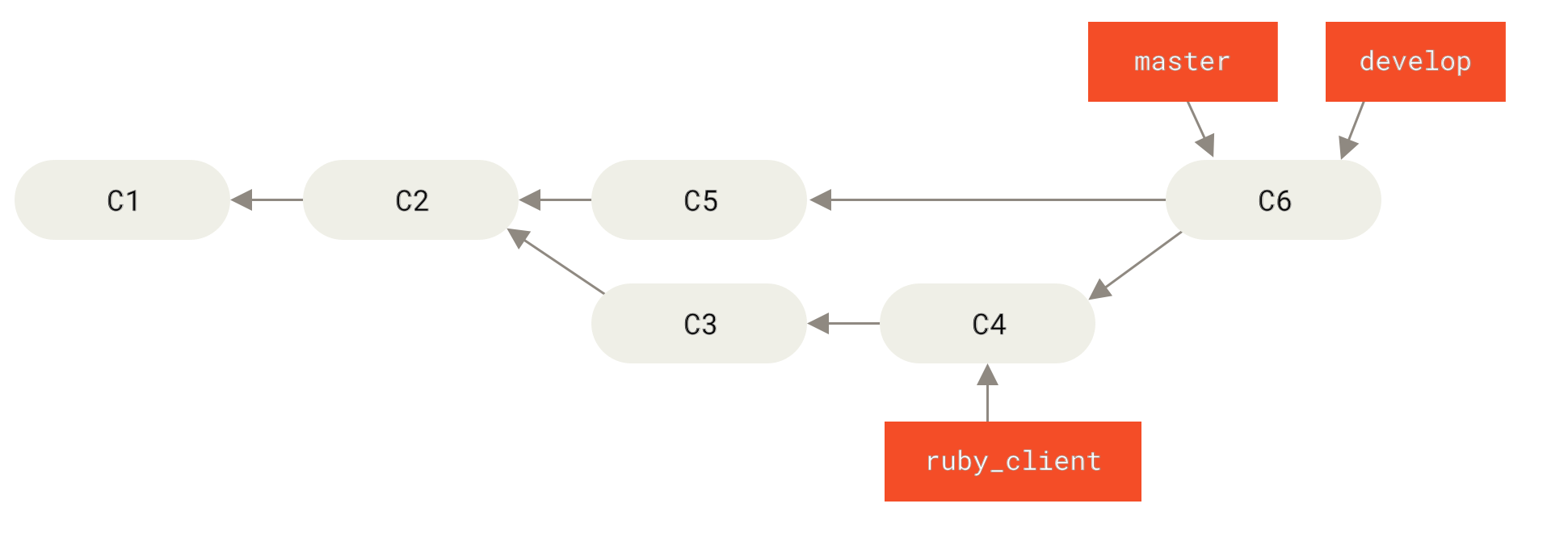

Each time you have a new topic branch to merge in (Before a topic branch merge.), you merge it into develop (After a topic branch merge.); then, when you tag a release, you fast-forward master to wherever the now-stable develop branch is (After a project release.).

This way, when people clone your project’s repository, they can either check out master to build the latest stable version and keep up to date on that easily, or they can check out develop, which is the more cutting-edge content.

You can also extend this concept by having an integrate branch where all the work is merged together.

Then, when the codebase on that branch is stable and passes tests, you merge it into a develop branch; and when that has proven itself stable for a while, you fast-forward your master branch.

Large-Merging Workflows

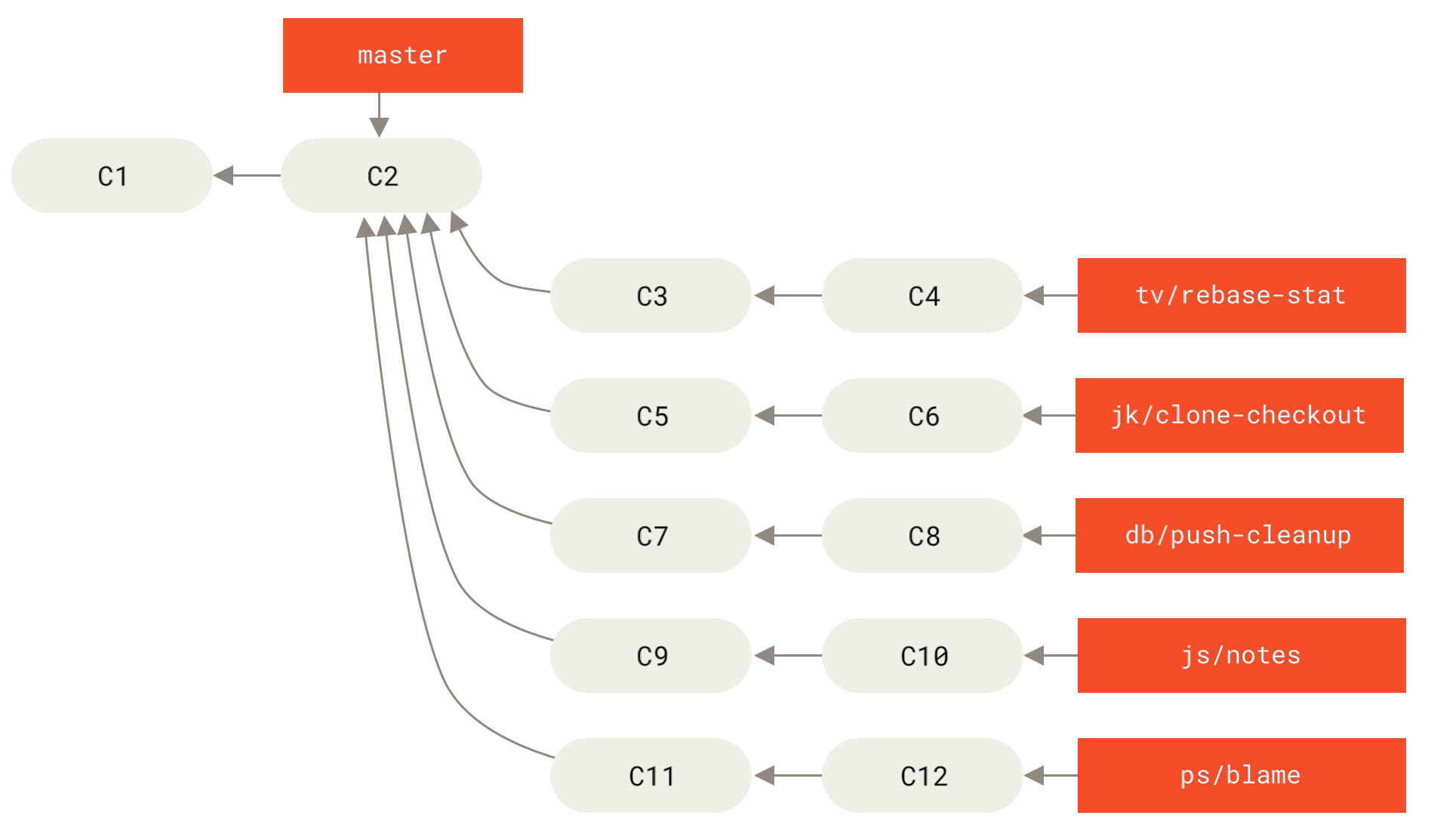

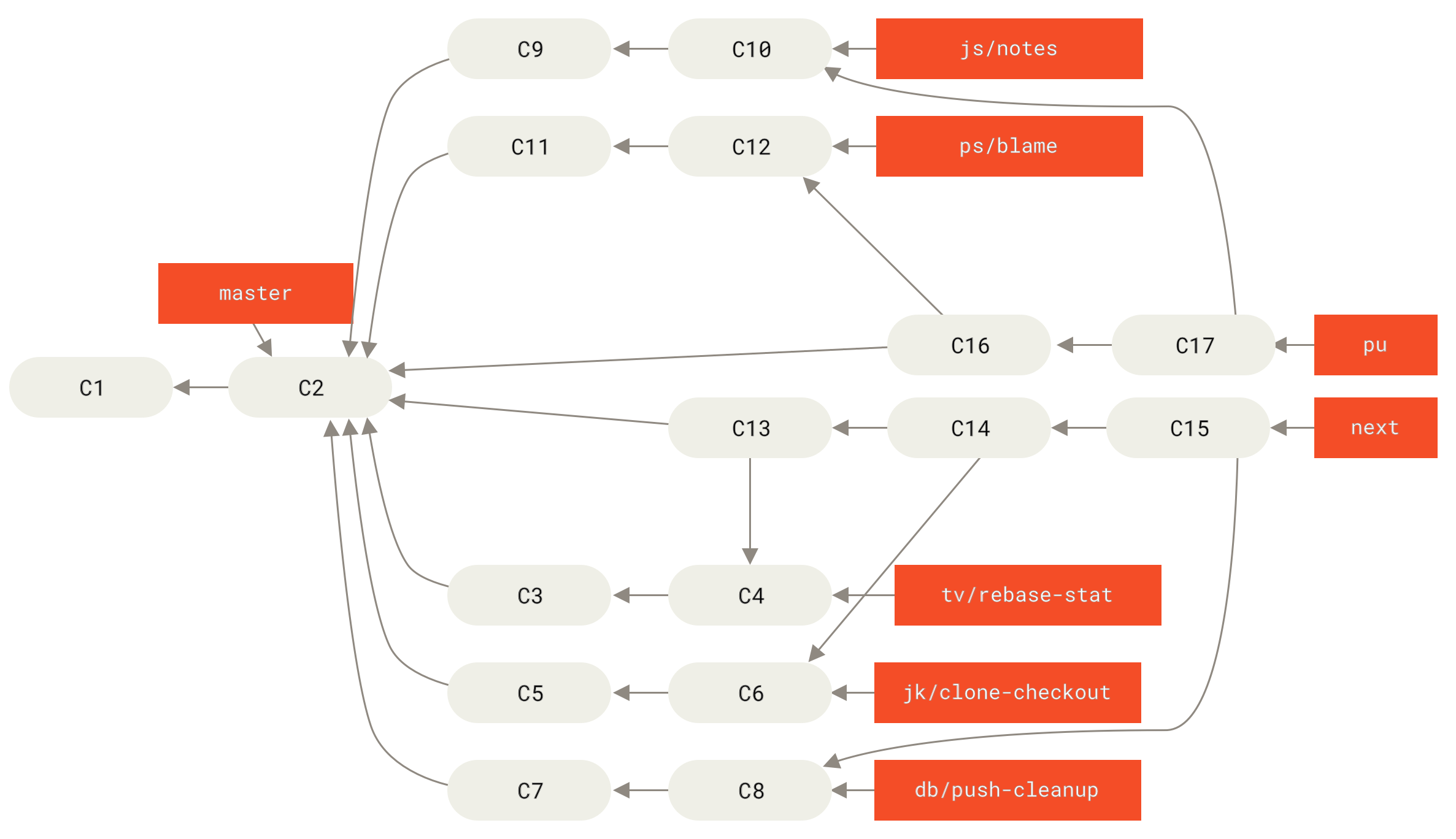

The Git project has four long-running branches: master, next, and pu (proposed updates) for new work, and maint for maintenance backports.

When new work is introduced by contributors, it’s collected into topic branches in the maintainer’s repository in a manner similar to what we’ve described (see Managing a complex series of parallel contributed topic branches.).

At this point, the topics are evaluated to determine whether they’re safe and ready for consumption or whether they need more work.

If they’re safe, they’re merged into next, and that branch is pushed up so everyone can try the topics integrated together.

If the topics still need work, they’re merged into pu instead.

When it’s determined that they’re totally stable, the topics are re-merged into master.

The next and pu branches are then rebuilt from the master.

This means master almost always moves forward, next is rebased occasionally, and pu is rebased even more often:

When a topic branch has finally been merged into master, it’s removed from the repository.

The Git project also has a maint branch that is forked off from the last release to provide backported patches in case a maintenance release is required.

Thus, when you clone the Git repository, you have four branches that you can check out to evaluate the project in different stages of development, depending on how cutting edge you want to be or how you want to contribute; and the maintainer has a structured workflow to help them vet new contributions.

The Git project’s workflow is specialized.

To clearly understand this you could check out the Git Maintainer’s guide.

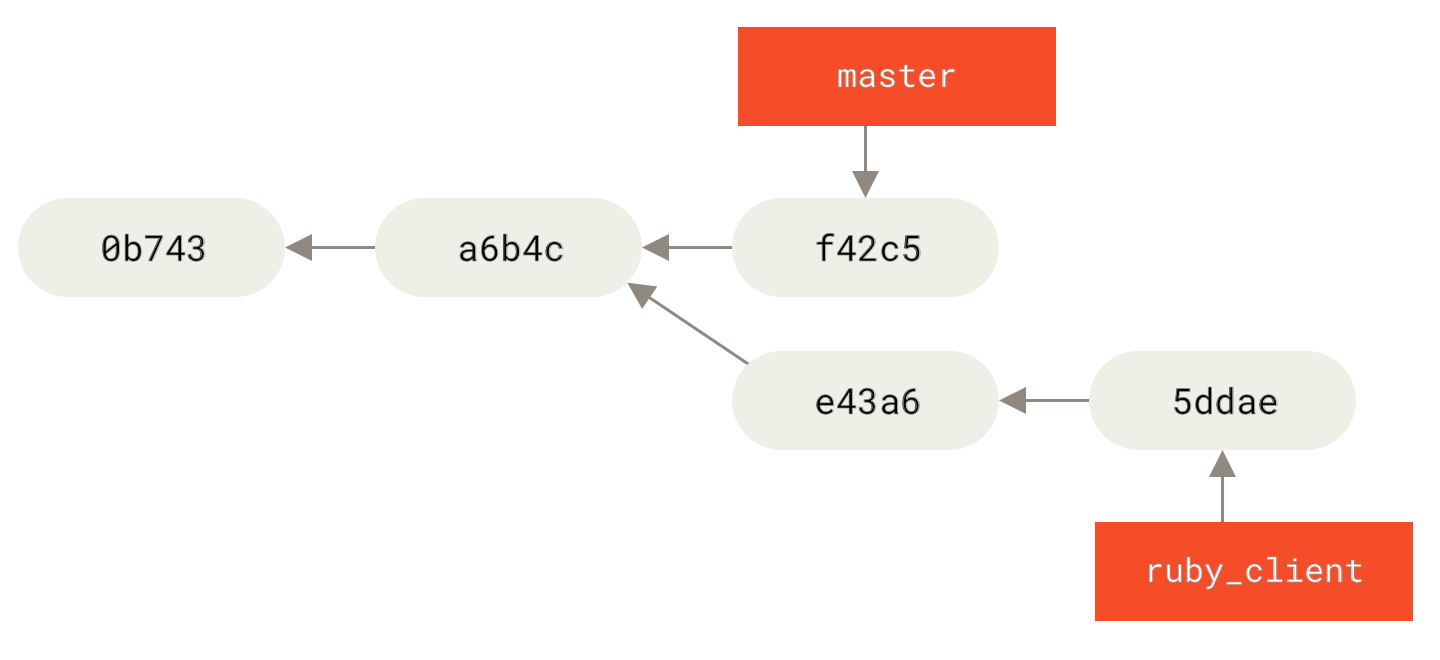

Rebasing and Cherry-Picking Workflows

Other maintainers prefer to rebase or cherry-pick contributed work on top of their master branch, rather than merging it in, to keep a mostly linear history.

When you have work in a topic branch and have determined that you want to integrate it, you move to that branch and run the rebase command to rebuild the changes on top of your current master (or develop, and so on) branch.

If that works well, you can fast-forward your master branch, and you’ll end up with a linear project history.

The other way to move introduced work from one branch to another is to cherry-pick it. A cherry-pick in Git is like a rebase for a single commit. It takes the patch that was introduced in a commit and tries to reapply it on the branch you’re currently on. This is useful if you have a number of commits on a topic branch and you want to integrate only one of them, or if you only have one commit on a topic branch and you’d prefer to cherry-pick it rather than run rebase. For example, suppose you have a project that looks like this:

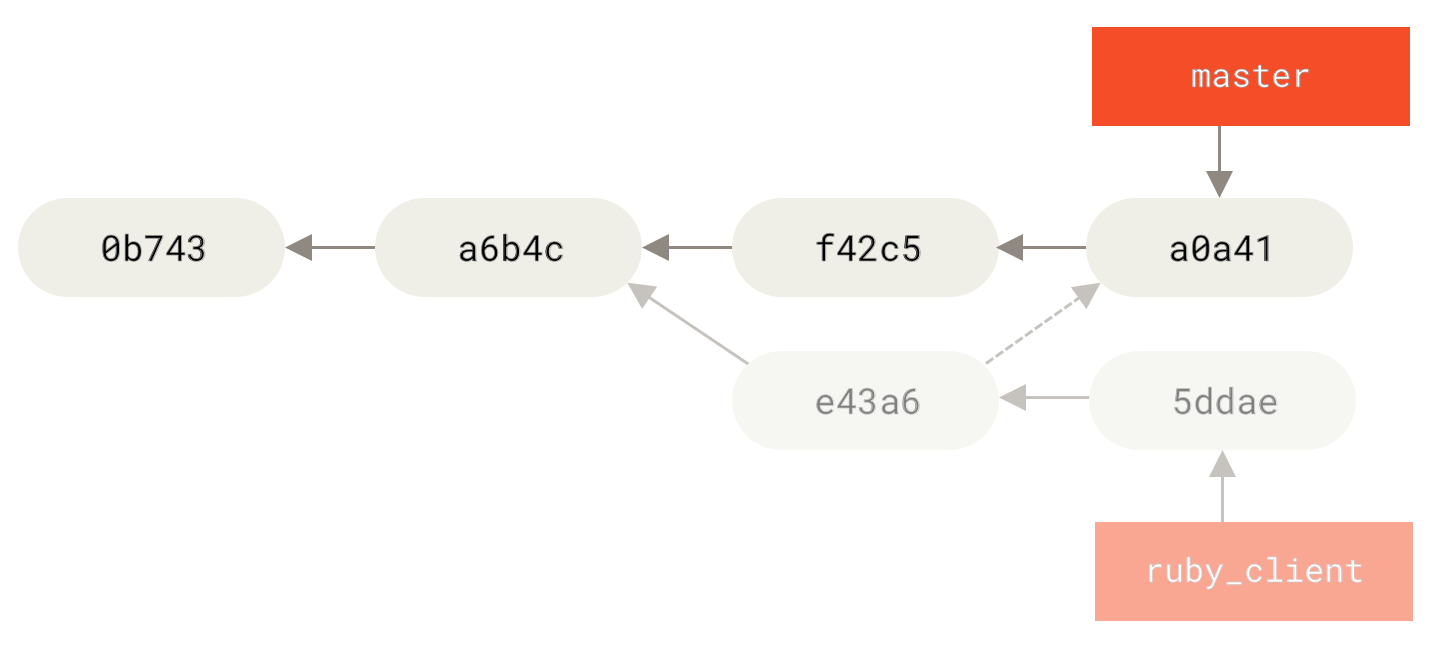

If you want to pull commit e43a6 into your master branch, you can run

$ git cherry-pick e43a6 Finished one cherry-pick. [master]: created a0a41a9: "More friendly message when locking the index fails." 3 files changed, 17 insertions(+), 3 deletions(-)

This pulls the same change introduced in e43a6, but you get a new commit SHA-1 value, because the date applied is different.

Now your history looks like this:

Now you can remove your topic branch and drop the commits you didn’t want to pull in.

Rerere

If you’re doing lots of merging and rebasing, or you’re maintaining a long-lived topic branch, Git has a feature called ``rerere'' that can help.

Rerere stands for ``reuse recorded resolution'' — it’s a way of shortcutting manual conflict resolution. When rerere is enabled, Git will keep a set of pre- and post-images from successful merges, and if it notices that there’s a conflict that looks exactly like one you’ve already fixed, it’ll just use the fix from last time, without bothering you with it.

This feature comes in two parts: a configuration setting and a command.

The configuration setting is rerere.enabled, and it’s handy enough to put in your global config:

$ git config --global rerere.enabled true

Now, whenever you do a merge that resolves conflicts, the resolution will be recorded in the cache in case you need it in the future.

If you need to, you can interact with the rerere cache using the git rerere command.

When it’s invoked alone, Git checks its database of resolutions and tries to find a match with any current merge conflicts and resolve them (although this is done automatically if rerere.enabled is set to true).

There are also subcommands to see what will be recorded, to erase specific resolution from the cache, and to clear the entire cache.

We will cover rerere in more detail in Rerere.

Tagging Your Releases

When you’ve decided to cut a release, you’ll probably want to assign a tag so you can re-create that release at any point going forward. You can create a new tag as discussed in Git Basics. If you decide to sign the tag as the maintainer, the tagging may look something like this:

$ git tag -s v1.5 -m 'my signed 1.5 tag' You need a passphrase to unlock the secret key for user: "Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com>" 1024-bit DSA key, ID F721C45A, created 2009-02-09

If you do sign your tags, you may have the problem of distributing the public PGP key used to sign your tags.

The maintainer of the Git project has solved this issue by including their public key as a blob in the repository and then adding a tag that points directly to that content.

To do this, you can figure out which key you want by running gpg --list-keys:

$ gpg --list-keys /Users/schacon/.gnupg/pubring.gpg --------------------------------- pub 1024D/F721C45A 2009-02-09 [expires: 2010-02-09] uid Scott Chacon <schacon@gmail.com> sub 2048g/45D02282 2009-02-09 [expires: 2010-02-09]

Then, you can directly import the key into the Git database by exporting it and piping that through git hash-object, which writes a new blob with those contents into Git and gives you back the SHA-1 of the blob:

$ gpg -a --export F721C45A | git hash-object -w --stdin 659ef797d181633c87ec71ac3f9ba29fe5775b92

Now that you have the contents of your key in Git, you can create a tag that points directly to it by specifying the new SHA-1 value that the hash-object command gave you:

$ git tag -a maintainer-pgp-pub 659ef797d181633c87ec71ac3f9ba29fe5775b92

If you run git push --tags, the maintainer-pgp-pub tag will be shared with everyone.

If anyone wants to verify a tag, they can directly import your PGP key by pulling the blob directly out of the database and importing it into GPG:

$ git show maintainer-pgp-pub | gpg --import

They can use that key to verify all your signed tags.

Also, if you include instructions in the tag message, running git show <tag> will let you give the end user more specific instructions about tag verification.

Generating a Build Number

Because Git doesn’t have monotonically increasing numbers like 'v123' or the equivalent to go with each commit, if you want to have a human-readable name to go with a commit, you can run git describe on that commit.

In response, Git generates a string consisting of the name of the most recent tag earlier than that commit, followed by the number of commits since that tag, followed finally by a partial SHA-1 value of the commit being described (prefixed with the letter "g" meaning Git):

$ git describe master v1.6.2-rc1-20-g8c5b85c

This way, you can export a snapshot or build and name it something understandable to people.

In fact, if you build Git from source code cloned from the Git repository, git --version gives you something that looks like this.

If you’re describing a commit that you have directly tagged, it gives you simply the tag name.

By default, the git describe command requires annotated tags (tags created with the -a or -s flag); if you want to take advantage of lightweight (non-annotated) tags as well, add the --tags option to the command.

You can also use this string as the target of a git checkout or git show command, although it relies on the abbreviated SHA-1 value at the end, so it may not be valid forever.

For instance, the Linux kernel recently jumped from 8 to 10 characters to ensure SHA-1 object uniqueness, so older git describe output names were invalidated.

Preparing a Release

Now you want to release a build.

One of the things you’ll want to do is create an archive of the latest snapshot of your code for those poor souls who don’t use Git.

The command to do this is git archive:

$ git archive master --prefix='project/' | gzip > `git describe master`.tar.gz $ ls *.tar.gz v1.6.2-rc1-20-g8c5b85c.tar.gz

If someone opens that tarball, they get the latest snapshot of your project under a project directory.

You can also create a zip archive in much the same way, but by passing the --format=zip option to git archive:

$ git archive master --prefix='project/' --format=zip > `git describe master`.zip

You now have a nice tarball and a zip archive of your project release that you can upload to your website or email to people.

The Shortlog

It’s time to email your mailing list of people who want to know what’s happening in your project.

A nice way of quickly getting a sort of changelog of what has been added to your project since your last release or email is to use the git shortlog command.

It summarizes all the commits in the range you give it; for example, the following gives you a summary of all the commits since your last release, if your last release was named v1.0.1:

$ git shortlog --no-merges master --not v1.0.1

Chris Wanstrath (6):

Add support for annotated tags to Grit::Tag

Add packed-refs annotated tag support.

Add Grit::Commit#to_patch

Update version and History.txt

Remove stray `puts`

Make ls_tree ignore nils

Tom Preston-Werner (4):

fix dates in history

dynamic version method

Version bump to 1.0.2

Regenerated gemspec for version 1.0.2

You get a clean summary of all the commits since v1.0.1, grouped by author, that you can email to your list.

Summary

You should feel fairly comfortable contributing to a project in Git as well as maintaining your own project or integrating other users' contributions. Congratulations on being an effective Git developer! In the next chapter, you’ll learn about how to use the largest and most popular Git hosting service, GitHub.